SF Performances’ popular concert/lecture series in Berkeley

Our appreciation for music often deepens with knowledge and familiarity. When a top Bay Area string quartet and a top musicologist join forces to combine concert hall with lecture hall, one can be sure of that deeper experience, and such was the case last Saturday, Jan. 11, when the Alexander String Quartet and composer/historian Robert Greenberg teamed up for a morning lecture/performance.

This was the culmination of a four-part series on Benjamin Britten and his contemporaries, titled “In a Time of War,” which began several weeks previously with a brilliant lecture on World War II as the milieu and backdrop of these quartets. This year was also Britten’s centenary, an opportunity to promote this composer Greenberg and the Alexander Quartet, in their latest of many fruitful collaborations thta began 15 years ago in Berkeley.

Greenberg prepared us for two seminal experiences by composers who admired each other, Britten and Dmitri Shostakovich. Neither expected to live beyond the work, as Britten’s heart was giving out and Shostakovich was preparing for suicide (which a watchful friend thankfully averted). As such, each quartet is a last statement of self on the canvas of a difficult life. Shostakovich’s Quartet No. 8 is a hair-raising work of despairing beauty and biting sarcasm, while Britten’s Quartet No. 3, written after a long absence from the quartet form—30 years after his Quartet No. 2—unfolds in an arch whose unearthly capstone mimics Mahler’s harbinger of death, the nightingale, according to Greenberg.

But before immersing us in these last rites, Greenberg, an accessible and salty lecturer, joked about events in his home state, New Jersey, and then bare-knuckled his way into Russian politics.

“School children late to school? Bridge lanes closed? Is this scandal? New Jersey, you’re not what you used to be. Now, Orthodox Jersey Jews sell kidneys from Palestinians… that’s scandal!” He then turned to Russia.

“Art, politics and current events make strange bedfellows… Of 1990’s Russia, journalist David Remnick said, ‘It was Oz.’ To understand Shostakovich, we need to understand his time and place.”

Greenberg went on to describe the chancy life of an artist in Stalinist Russia. Shostakovich was twice denounced, rose to fame, and saw many composer friends shot or imprisoned. “He survived because he was perceived as the holy village idiot, offering his criticisms to God, rather than to the State.”

Greenberg spoke of the autobiographical essence of the work, which begins with a four-note motif, D, E flat, C, B. In German notation that is DSCH, letters that Dmitri Shostakovich took as his monogram (and DSCH is the title of a journal devoted to the composer). That motif, at times funereal and at times manic, formed the backbone of the quartet, and arrayed over it were quotes from his long career. Shostakovich wrote it in only three days after visiting the devastation of Dresden. “It is dedicated to the memory of the composer,” claimed Greenberg, “Not to the victims of war, as the State claims. He uses passages from his Symphonies and from his 1944 Piano Trio.”

That quote was from a Klezmer folk song, prominent from cello in the Piano Trio No. 2 and written high in the first violin part for his later Quartet No. 8. “Shostakovich once wrote that Jewish music is laughter through misery and tears. This waltz is a Totentanz, a dance of death. It is a danse macabre.” He then gestured to the ASQ, who played both the earlier slow version and then the manic waltz from the quartet.

“That quotation is as clear as a Saran Wrap toga, my friends.” Greenberg’s own remarks clearly followed that Klezmer recipe, adroit and self-mocking.

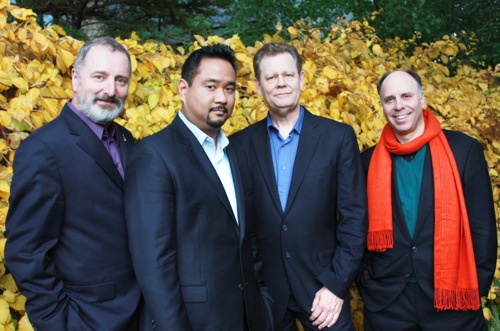

Then they performed the work in its entirety. Cellist Sandy Wilson entered with the somber four-note theme, followed by violist Paul Yarbrough and violinists Frederick Lifsitz and Zakarias Grafilo. Each of these musicians brings a hefty sound, creating absolute clarity of line while developing chords of smooth blend and disturbing breadth.

Later came the alarming “knock on the door” motif, three abrupt strokes on the heels of a thinly keening violin. It is the personification of the wolf at the door (or the KGB), with its immediate menace.

The great cellist Mstislav Rostropovich knew both composers, and each wrote cello suites for him. “It was hard to find two such different men,” he once said. “I remember his [Shostakovich’s] deeply tragic sarcasm… and the strength and sincerity of Britten.” Each dedicated works to the other.

After wintry Russian bite, Britten sounded drear as British weather, with long moments of silence and lots of air. Greenberg described the regular reversal of foreground and background as an ingenious lapping quality, much like the waves on Britten’s beloved coastal village of Aldeburgh. Viola and second violin figured prominently, twining and mirroring, as violin and cello offered cryptic comments. The center of the work, the “capstone” according to Greenberg, implied the language of birds and perhaps a transition to a higher plane, while the final movement, “La Serenissima,” featured a disturbing serenity, high and dissonant.

Britten wrote much of this with his left hand, as the once-concert pianist suffered a stroke during heart surgery. Though completely lucid, his health rapidly declined. He was just able to finish this final quartet, which premiered fifteen days after his death.

Britten wrote much of this with his left hand, as the once-concert pianist suffered a stroke during heart surgery. Though completely lucid, his health rapidly declined. He was just able to finish this final quartet, which premiered fifteen days after his death.

—Adam Broner

Photo top of Robert Greenberg; below, of the Alexander String Quartet, photos courtesy of SF Performances.