Local composers having fun

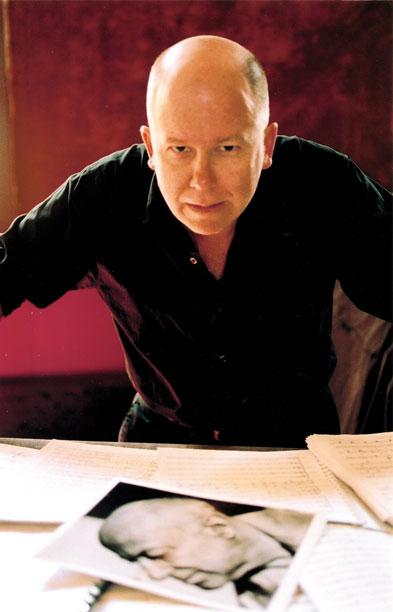

Mark Alburger, a local composer of note, has long cut a colorful figure in the Bay Area’s music and opera scene. In his latest experiment, The Opus Project, he takes a decidedly different format than his usual, or from most concerts for that matter.

Rather than pose a concert around a genre or theme, Alburger decided to create a series of monthly concerts around opus numbers, focusing on twentieth century and contemporary composers, performed as a timeline. Their first concert, a month ago, consisted of the first known works of these composers—Opus 1, as they are catalogued.

Last Sunday’s concert, held at the Berkeley Arts Festival storefront on University Avenue, was “Opus 2,” a second work from stalwarts of the repertoire, followed by living composers. Though these pieces were divergent, the program did evolve along two themes: a sense of music history as a living continuum, and widely differing works by composers at the beginning of their careers. There was a sense of youthful art, of possibilities and the pregnant presence, of wrestling with similar issues.

Last Sunday’s concert, held at the Berkeley Arts Festival storefront on University Avenue, was “Opus 2,” a second work from stalwarts of the repertoire, followed by living composers. Though these pieces were divergent, the program did evolve along two themes: a sense of music history as a living continuum, and widely differing works by composers at the beginning of their careers. There was a sense of youthful art, of possibilities and the pregnant presence, of wrestling with similar issues.

Alburger, musical director of Goat Hall Opera/ San Francisco Cabaret Opera, has had several of his operas premiered by that company, which he runs with his partner, artistic director Harriet March Page. His pop/tragic opera, Of Mice and Men, his post-apocalyptic Antigone, and his recent Sex and the Bible all displayed a creative command of “tropes,” memes snatched without regard from the entire musical repertoire.

Describing himself as “…an eclectic composer of postminimal, postpopular and postcomedic sensibilities”, he is also the music director of the San Francisco Composers Chamber Orchestra, a group of composer-musicians who gather to perform their own new works, and a member of Composers, Inc.

But his other hat, as a lecturer in composition and music history, is what was most noticeable about the Opus Project. Not only were many students in attendance, hoping to score extra credit, but his analytical and humorous introductions lent themselves to a learning environment.

His pickup orchestra of unpaid professionals, amateurs, and composers was a nice leveling of the “playing” field. Their concert opened with a piano work, Alexander Scriabin’s Three Pieces, Op. 2 (of course) from 1889. Pianist Jerry Kuderna introduced it. “Scriabin was a 17-year-old influenced by Chopin with a generous dose of Russians… it is a collection of three interesting keys.” Indeed, Kuderna delivered the dreaminess of Chopin, if not his liquidity, with yearning phrases plowing their way up a steep hill. The Prelude was more optimistic, but with the restrained simplicity of a child. He ended with the dance-like weighting of a mazurka.

Soprano Sarita Cannon joined Kuderna for Arnold Schoenberg’s Erwartung from Four Songs, Op. 2 (1899), “…a tonal departure from his earliest stuff, but still tonal, and he has a way to go before we get to atonal,” according to Alburger.

A high point of the concert, Cannon’s voice was high and supple, crooning the complex and sweetened vowels of German with dry heights and thick lip-licking consonants. From the yearning of Scriabin we had evolved to a dreaminess that paralleled Debussy’s haunting sensuality.

We soon arrived at Anton Webern’s second work, In Swift Light Vessels Gliding (1908), which Alburger had rearranged for the occasion. “It just sounded weird, maybe because it’s a choral piece and we’re doing an orchestral version… He studied Mideast polyphony, but this is chromatic and atonal.” And yes, it was weird; finger popping bounces with atonal lines, a curious fish-fowl creature flopping out of fin de siecle waters and onto the shores of the twentieth century. But the motifs, which Alburger rewrote as flute duets, were sumptuous.

Mark took the piano for a duet with mezzo Harriet Page, singing Alban Berg’s melancholy Aus Dem Schmertz. Page inhabited the anguish beneath the symbolist poetry of slumber, dwelling on strange intervals as the piano added slow dissonances.

A video followed, Prokofiev’s Etude in D minor, which Mark described as reverse-channeling Philip Glass. Another enfante terrible, Prokofiev showed huge arc and complexity in his 1909 etude, but with a rolling understructure that may have inspired modern minimalists.

A short, bittersweet Shostakovich led into a lovely rendition of Three Songs by Barber, again sung by Sarita Cannon, and we had finally arrived at our living composers.

Pianist Allan Crossman wrote Influences in 1955. “This is music that I wasn’t hearing, and so I made it up,” said Allan, simply, as he sat at the piano. Each phrase had a playful lift to it, and there was a sense of wonder that he played with nostalgia. Now 71, he was 13 when he wrote this “Opus 2.” Very modern in the fifties, it is still jaunty as it breaks across keys and rhythms.

Pianist Allan Crossman wrote Influences in 1955. “This is music that I wasn’t hearing, and so I made it up,” said Allan, simply, as he sat at the piano. Each phrase had a playful lift to it, and there was a sense of wonder that he played with nostalgia. Now 71, he was 13 when he wrote this “Opus 2.” Very modern in the fifties, it is still jaunty as it breaks across keys and rhythms.

Michael Kimbell performed Dialogues for Two Clarinets (1968) with the help of fellow clarinetist Peter Brown. “I was 22 and a grad student, and my teacher asked me to write something ‘colorful.’” The five short duets were quick-witted and imagistic, partners chasing and tripping each other with sharp trills and nymphic panpipes.

Alburger included an early work of his, Suite (“Sol[ar]”) for Oboe, Piano and Percussion, but it was unfortunately in video form. I would have dearly loved to hear this pop/classical fusion live. Then Sheli Nan took the piano for her 1978 Bach Boogie Blues, which she described as combining elements “…from the ridiculous to the sublime.” And yes, it was a boogie-woogie version of Bach, balancing elegance with light-hearted jazz.

They closed with Sine Waves, a flute duet by Bruce Salvisberg that sharply recalled three moods.

This was an energetic and visceral way to experience artistic evolution, and the experiment continues next month with “Opus 3” at 2133 University Ave, in downtown Berkeley. If this is typical, one envies Alburger’s students.

—Adam Broner

Photo top of composer Mark Alburger; photo bottom of soprano Sarita Cannon.