At 79 years old, jazz legend Sonny Rollins plays with stamina, lungpower, and intellectual flexibility seldom seen or heard by horn players of any age. Backed by an all-star band consisting of Bobby Broom (guitar), Bob Cranshaw (bass), Kobie Watkins (drums), and Victor See-Yuen (percussion), his performance for Cal Performances at Zellerbach Hall on May 13 was a privilege of indescribable proportions.

The evening’s concert consisted of six tunes, beginning with the new Patanjali and ending with an unnamed monochordal piece filled with infinite improvisational possibilities. In between there was a blues piece (Mishi), a beautiful rendition of My One and Only Love, an uncomplicated and uninteresting jam in the middle of the program, and an original piece of little consequence as a penultimate choice. All this Rollins played with nonchalance and confidence through his very expressive tenor sax and his aging, slouched body, having derived his hunched posture from a lifetime of hanging a heavy instrument around his neck. Yet, colossal Sonny somehow makes the saxophone look small.

Sonny, called by some a “god” of jazz, and one of the fathers of bebop, wailed. Though he created tensions and resolutions by teasing chord changes with his improvisational genius, he maintained enough structure and foundation for the listener to stay with him—using repetitions of motifs and sequences to remind the audience where the improvisation began while leading to unexplored and completely unexpected harmonic territory. After Patanjali, Sonny talked about the joy he felt at being back in Berkeley. He told a story about a conversation he’d had in 1998, “just a few years ago.”

“Somebody asked me, ‘Sonny, what is global warming?’ ‘Look man, global warming is when you’re driving in the car and you’re eating something and then you throw the garbage out the window and it comes on the road and somebody else has to clean it up and that’s personal responsibility that the world has to have for everybody in it. See, so that’s global warming. Personal responsibility … OK, that’s enough preaching.”

Then Rollins’ all-star band proceeded to play a tropical-island I-IV-V progression that was exaggeratedly simple. So much so, that guitarist Bobby Broom seemed to struggle to find non-cliché improvisational ideas. This piece seemed uncharacteristic and a bit out of place amid the other classics attributed to Sonny’s name.

The quartet finished with a monochordal piece that featured all the players in the band and provided an improvisational canvas that could take many forms. By alternating 3/4 and 5/4 measures, Rollins reminded the listener of the multiple routes in rhythmic and melodic variation possible when playing the same repeating chords. With the absence of a progression, possibilities were endless. It’s like the analogy of the point: with just one point, you can travel in any direction; with two, you have to find creative ways of traveling the line between them without straying too far from the line.

The fact that the quartet’s last piece only offered one chord allowed Sonny to voraciously shed what seemed like endless musical variations in any direction. Applause erupted prematurely. Most of the audience leapt to their feet. An encore was demanded, but what we got was a wave from the band. And we understood with compassion that a concert from the venerable jazzman was a blessing.

How can he still be so on point, so intellectually and creatively sharp, so original and technically sound? How can he still be so on top of it? I hadn’t imagined that “Sonny still practices 8-12 hours per day,” as bassist Cranshaw confirmed backstage after the concert. A feat that seems supernatural, especially on tour.

After the concert and speaking with Rollins’ group, I felt a deep appreciation and admiration for their invaluable contributions to the music that makes my heart keep beating, that is, jazz.

—Martin Blank

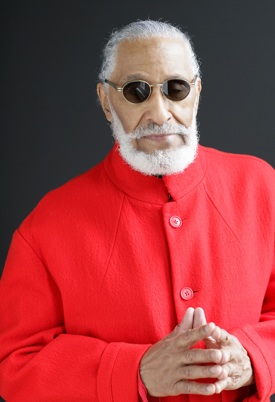

Photo of Sonny Rollins