From fluff to frozen in West Oakland.

Experts at reinvention, the West Edge Opera has returned for a summer festival in an industrial wasteland in West Oakland, the abandoned facilities of Pacific Pipe Company. This resilient opera company, formerly Berkeley Opera, has inhabited a series of venues over the last ten years, most recently at West Oakland’s abandoned train station for two startling and brilliant summers. Dealing with the freedoms and rigors of being “on the road,” has transformed them into a festival format with three complete operas rotating across three weekends. Like the SF Opera, that ambitious plan has a core of solid musicians, separate casts and directors, and quick-changing sets.

Under Artistic Director Mark Streshinsky and Music Director Jonathan Khuner, this nimble company continues to mount budget operas with extravagant music, and to test our sense of adventure. That “edge” has been visible both in the unusual venues and in the dramatic risks they take, in a repertoire that spans from Baroque operas on period instruments to contemporary operas.

They recently finished the festival with two very different works. On Saturday, Aug. 19, we saw The Chastity Tree by Vicente Martin y Soler, a seldom-seen piece by a composer who was quite popular in his time and a contemporary of Mozart.

One would have been surprised how much this sounded like Mozart. It held some of the language that Mozart used: stately progressions, coy instrumentation, an ear for simplicity and some divine trios. From this buffo opera, it would be hard to tell whether Mozart borrowed ideas from Martin y Soler or vice versa.

Adding to the similarities, Martin y Soler wrote his music to a libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte, the same man who collaborated with Mozart and wrote the scripts for Don Giovanni and The Marriage of Figaro.

But there were also differences, and I suspect the audiences of that era would have found them striking. The Chastity Tree was more decorative and the variations had less of Mozart’s touch and more of the baroque era. And there were more recitatives and fewer solos, with a major exception. That was a powerhouse Aria-to-End-All-Arias sung by Nikki Einfeld as the goddess Diana. And her later aria, “Take my soul and my love,” was a slow, sweet showstopper.

Streshinsky, who directed this opera, stressed the absolute fluff of this naughty comedy, exaggerating a lot but rendering one thing quite explicitly: that the risqué operas of 1750 make modern Americans look like… well, Puritans. Christine Brandes played Cupid as a cross-dressing demigod in an outfit so outlandish it was spooky. Her voice was an appropriate vehicle for a divine being, pure and teasing and outsized despite the odd acoustics of the huge space.

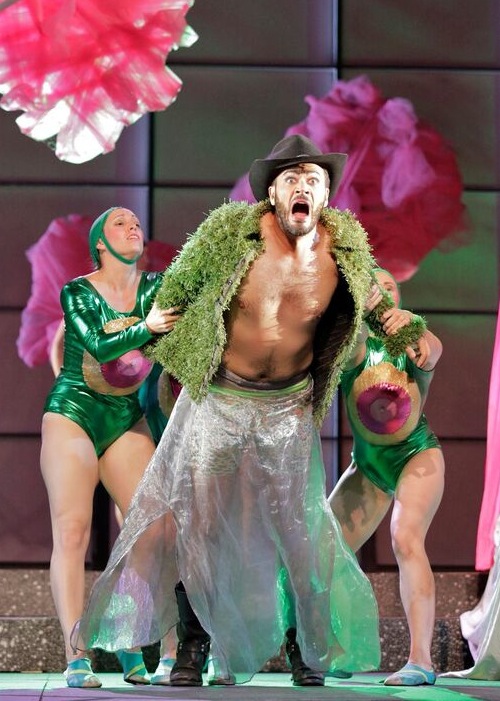

As Doristo, a shepherd captured by Diana’s troops to guard the Tree, Malte Roesner also played it larger-than-life, appealing to any and every sex with his rich bass voice, cowboy hat, boots, and sheer skirt (!).

The two tenors (and under their clear plastic raincoats was written “Tenor” and “The other tenor”) were Kyle Stegall and Jacob Thompson. Stegall’s voice was open and unselfconscious in “Her eyes were full of love and joy,” and his “Addio” and “Pieta” were both magical. Together, those three male voices had some exquisite moments of harmony, while opposite them were three warriors of Diana, all fine singers who knew how to bring on the comic acting. Maya Kherani had a bright and supple top register and fetching acting, Molly Mahoney had a festive and lyric soprano and looked quite capable with a spear, and Kathleen Moss added chocolaty alto notes and stole the show with her fear of Diana and reluctance to dive in to her own sexuality.

Tying the action together were the ten dancers of the Tree, attentive weathervanes to the twists and turns of the plot. They were dressed in scintillant greens and big red uni-boobs, each with a flashing light like the famed Carol Doda sign in SF’s red light district. As they wended their way up and down the ladders of the impromptu set, readied to hurl “apples” at unchaste offenders, or wound themselves around intruders as soft vegetation, these dancers gathered the slow action into a whole, with excellent choreography by Sarah Berges and costumes by Christine Crook.

And after Fluffy?

Sunday, Aug. 20, was the last performance of the festival. Frankenstein, by Libby Larson, was a modern work of ice and fury that questioned some of the concepts of opera. It combined excellent singers, strong musicians, a fascinating score, a powerful tale and an arresting dancer/choreographer into a whole. But that whole was less than its parts.

Larsen’s version of Frankenstein took an instructive story about a parent who withholds his love, and combines that with the corrosive effects of secrets. It should have been a grand tragedy, as was Mary Shelley’s original book, but there was something about the construction that did not invite us into the emotions.

While each element was compelling, the dramatic action depended on short scenes that were like careful postcards, full of tension but static as the ice floes that began and ended this opera. Larsen’s music was the action, at times disturbing and at times evocative, a fury of quick gestures and slow spellbinding tinctures. But her writing for the voice was angular and belligerently un-melodic and it numbed that musical action.

The central part of this work stepped outside of the usual confines of opera to showcase a dance performance by Gary Morgan, a noted choreographer whose sharp isolations and rubbery flow are straight out of turf dancing, Oakland’s contribution to World street dance. His stuttering fluidity made his dance a good fit for a creature that was part human and part created, referencing an innate fear that we will be destroyed by what we create – whether that is machines or Frankenstein or even progeny! Morgan’s dance flowed across the uneven terrain of the musical overture, translating its disparate moods into his own language of extensions and dislocations, as behind him was projected a video of the world through the eyes of Frankenstein (video art by Jeremy Knight).

That central piece was impressive, and West Edge Opera has kept another promise to push our boundaries.

—Adam Broner

Photo above of Malte Roesner as Doristo in The Chastity Tree, below of Frankenstein at the opening in the Pacific Pipe Co. warehouse; both photos by Cory Weaver.