There’s no doubt that the audience loves Bill Irwin. All he has to do is pull on a pair of baggy pants and the audience cheers. There’s also no doubt that Bill Irwin loves Samuel Beckett. These two premises serve as the basis for On Beckett, the one-man investigation of the renowned Irish writer by Bill Irwin that is running at A.C.T.’s The Strand Theater through January 22.

Irwin has been reading Beckett’s texts since his college days and, in concert with A.C.T., has pursued examining Beckett’s texts in various performances for the past two decades. In 2001, Irwin performed Beckett’s Texts for Nothing, a series of 13 monologue-like texts by single – and solitary – voices. And in 2012 he performed in A.C.T.’s production of Endgame, directed by Carey Perloff.

Irwin performed Vladimir in the acclaimed 2009 Broadway revival of Waiting for Godot, with Nathan Lane, John Goodman and John Gover. And he performed Lucky way back when.

Those are only the public signs of what Irwin understands of Beckett. The current production is the next step in the evolution of a theatrical monologue begun in Seattle in 2014. What the current production shows, however, is that it’s possible to love something too much. To love something so much that one’s adulation obscures the virtues and beauties of the original.

The likely idea that Irwin pursues in On Beckett is that Beckett’s spare and absurdist speech can be interpreted by physical comedy. The idea is easily supported by Beckett’s life and work. Beckett’s language is best understood spoken. The disruptions of thought, the chaos of uncertainty that the texts portray are often best understood in the hesitations and ramblings of speech. Then they become more accessible. It is, after all, how we speak to each other in everyday life, through our unedited and grammatically unpolished conversations.

And it’s often pointed out that Beckett’s family frequently attended the popular theater found in the variety halls of Dublin, and that Beckett loved the “clown” performers of silent film, Chaplin and, even more, that master of physical comedy, Buster Keaton.

Further, there is an undeniable comic streak to the absurd, which when language fails, can be found in physical gesture.

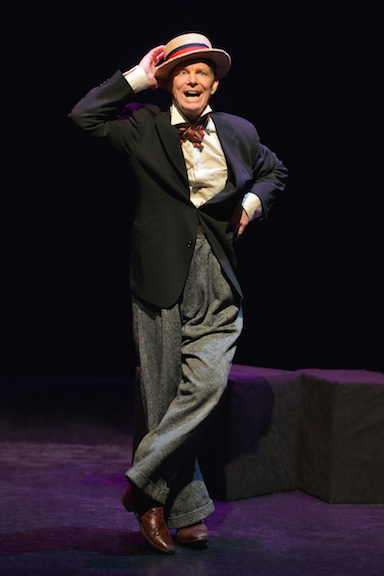

Irwin is a brilliant practitioner of physical movement. The flexibility and muscular control of his body allows him to float into easily recognizable emotional states. All of a sudden he is the desolate clown figure, in his tipped bowler hat and sunken shoulders, lines of distress displayed in the fallen corners of his mouth and eyebrows. He can just as convincingly settle his body into joy. What makes his portrayals humorous is that the emotion is exaggerated just past the acceptable. What is displayed is a caricature, something on the other side of believable.

So why didn’t Irwin’s performance work as effectively as it might have? I put it down to Irwin loving too much and trying too hard. Taking the spareness of Beckett’s language and embroidering it too incessantly, both with physical gesture and with the modulations of his voice. The text collapsed, and my viewer’s fascination shifted to Irwin’s skills. I heard only sounds resembling words, and instead was led to read the movements. The movements were entertaining but seemed to have little to do with the language, which had lost its accessibility.

It was like decorating a Craftsman-designed table with Baroque artifacts. The artifacts grab and retain our attention, while the table becomes a mere support, invisible, the elegance of its lines lost.

With about 40 percent less gesture and 30 percent less vocal modulations, the two theatrical ideas might have more comfortably melded into the performance of the year.

– Jaime Robles

On Beckett with Bill Irwin continues at The Strand in San Francisco through January 22. For information and tickets visit act-sf.org.

Photo: Tony Award–winner Bill Irwin returns to American Conservatory Theater in “On Beckett” at A.C.T.’s Strand Theater. Photo by Kevin Berne.