When Camille A. Brown talked about the process behind her dance piece, BLACK GIRL: Linguistic Play, in her TED Talk, she described performing the initial choreography at schools. Before each performance her dancers would ask the audience, “What do you think of when you hear the words ‘black girl’?” She was shocked and pained by the negative response of one group of students, and for a moment considered not performing. But when she looked out at the sea of mostly white faces, she saw among them a few brown ones, and knew she had to perform.

After the performance she asked the audience what they felt her dancing said. One word stood out among their responses: play. And, yes, that was what she wanted her dancing to communicate.

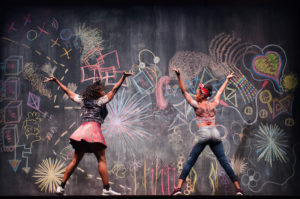

BLACK GIRL: Linguistic Play was presented by CalPerformances in the Zellerbach Playhouse this past weekend, and it was the season’s most delightful moment of dance. It began with a solo by Camille Brown on a stage with several raised and amplified platforms. A large chalkboard stood at the back of the stage and was decorated with a chaos of bright, childlike designs – flowers, stars, triangles, a pair of roller skates and more. Brown’s solo was introduced and then accompanied by the bluesy jazz music of bassist Robin Bramlett and pianist Scott Patterson.

The solo had the ambling quality of a child preoccupied with her imagination, bored with solitude and restless in foot and body. Brown peppered this daydreaming with volatile rhythmic dances, creating patterns of rhythm on the platforms and raising clouds of chalk dust as she stamped and tapped her trainers across the floor. Small, fleet and endowed with endless energy, she conjured up the memories of childhood in all its complexities, joys and confusions.

She was soon joined by Catherine Foster, and the two of them rocked the stage with synchronous rhythmic tapping, stomping, slapping and patting. The duet combined the intricate hopping of Double Dutch jump rope and the hand clapping of Nursery Rhymes. Both of which were reminiscent of Juba dancing, or hambone, the communal dance form that developed among slave communities in response to the prohibition against drumming inflicted on them by white masters. Juba dancers replaced the sound of the drums with stomping and clapping hands and parts of body.

Mayte Matalio and Beatrice Capote performed the piece’s second duet, which told the story of two sisters, one older and bolder, the other younger and admiring. Sitting in front of an imaginary television they react to an unseen drama. Older sister (Matalio) in her jeans is in the throes of growing up, her body doing things she has no control over, though joy permeates her every expression. Younger sister (Capote) in her short plaid skirt tries to emulate her sister’s glamor but, failing, falls into dismay. Sibling rivalry and competition raise their fiery heads. The two girls catapult through the rapidly shifting emotions of childhood, transforming the body into a language of dance that is unmistakable in its meaning. We believe the dancers’ portrayals entirely, while at the same time knowing they are adult women.

The third duet was between Kendra Dennard and Camille Brown. Dennard, tall and willowy, becomes a child full of imagination and an inscrutable tristesse. She plays with chalk as if it were a magic powder, capable of mysterious powers. Brown becomes her mother, quiet and soothing, pulling her lonely child into the warmth of understanding.

All of these parts remained clear within Brown’s exuberant and very demanding choreography. Brown claims BLACK GIRL: Linguistic Play is not a political piece, and that is easy to believe, despite the title, which makes a claim for identity politics. What Brown does instead is present the humanity of childhood in all its emotional vulnerability and physical vigor. And in doing so, she whisks away the rigidity and ignorance of stereotypes and highlights the capacity of dance and the body to provide compassionate meaning with all the subtlety of the most delicate and precise language.

– Jaime Robles