Defying genres and gravity

Thirteen performers cast a spell of darkness and dislocation last Saturday at Zellerbach Hall, where Cal Performances invited a group to do what they called “blurring boundaries.”

Defying the usual artistic genres, Circa, an Australian circus troupe, joined forces with two opera singers, director Yaron Lifschitz and composer Quincy Grant to reinvent Claudio Monteverdi’s early opera, Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria. Written in 1639, and based on Homer’s towering epic, this is one of the earliest of operas and helped to cement the art form, but it is seldom mounted today.

Lifschitz and Grant mined the natural affinity between the expressive power of movement and the raw emotions of opera to create their adaptation, Il ritorno, using four long excerpts from the Monteverdi opera and bridging them with passages of electronic synthesizer and a long cello solo.

What is unusual about this pairing of genres is that the movement is based on circus acrobatics, not traditional dance, much as Cirque du Soleil creates narratives to tie together their feats of strength and balance.

And rather than focus on the happily ever after of Ulysses’ homecoming after war and wandering, this narrative steeped us in the grief of a long separation, of creating the myth of home to sustain one’s spirits, of forces beyond our control. That emphasis enlarged the tale of Ulysses into a story that could be retold by the 65 million people displaced by today’s wars. In the words of the director, “In this circus-opera, history, antiquity, and the current waves of refugees who search for home all meld together into bodies, voices and music.”

In a very dark theater, the stage slowly lightened enough to see seven figures standing against a black wall. They began to move as the harpsichord began the prelude with bright spangling notes and plaintive chords.

The lighting was low and pointed throughout, creating exaggerated shadows and the intimacy of a black box theater, and subtly shrouded around the edges by fog. Two singers and four musicians sat onstage – cello, violin, harp and harpsichord – turning the piano trio of classical music into a vehicle suited for Monteverdi’s era.

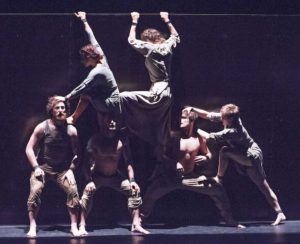

As the dancers began to move, we became aware that they were creating a language to fit the ancient story, a language of loneliness and loss, of intimacy and comfort. There was deep isolation in the shadowed tableaux, and figures curled into themselves, and pairs of dancers that helped to hold each other up, and the sense that the gravity which rules this world was fluid and dreamlike.

At one point they took turns wrenching the limbs of one of the male dancers into uncomfortable positions, and he stood there like some blighted tree, and that became a literal and metaphorical description of dislocation. Then harp and harpsichord joined together, a texture like lights along a garden path, and the baritone entered on “Dormo ancora,” (Do I yet sleep?).

Benedict Nelson sang the part of Ulysses with smooth, mouth-filling vowels, a “cream cheese” baritone. Despite that round smoothness, he created a feeling that homecoming was not quite real, but yet another weary dream.

Kate Howden was his counterpart as Penelope, the wife who waits twenty years for her husband’s return, weaving by day and unraveling by night. Her mezzo voice had a shrubby huskiness and a cavernous interior, and that somehow swallowed us and the room, so that we sat in her darkness.

Amid the ugliness of grief there was also grace and abandon and the comfort of touch. Dancers twisted and untwined on slender ropes, perhaps Penelope’s weaving or threads of hope or just a simple suspension of the body between ground and obscurity. And in addition to fluid leaps and rolls and falls, they clambered over and around each other in shared unbalance, and tossed and caught each other in glee, and climbed past each other to dizzy-making tiers.

There was a long cello solo performed by Pal Banda, and violin and viola both by Nicholas Bootiman and more exquisite pairings of harp and harpsichord performed by Cecilia de Santa Maria and Natalie Murray-Beale, respectively. And between the arias were interludes of synthesizer with dance beats and what sounded like rasps and even the stutter of guns.

At the end, the dancers helped each other off-stage in pairs.

This was an expressive and thought-provoking performance, and, while boundaries may have been blurred, each art form gave us a deeper appreciation of the other.

—Adam Broner

Photos by Tristram Kenton.