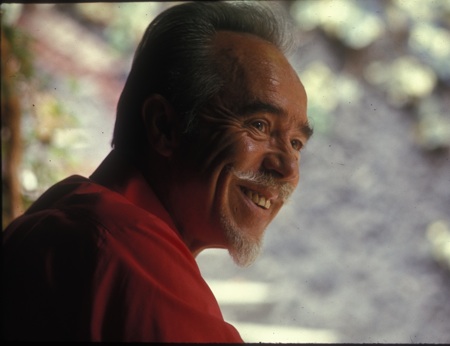

Celebrating a shy purist

Conlon Nancarrow, a composer fascinated by complex rhythms and the play of multiple tempos, would have celebrated his centennial last month. Living in some obscurity, he was rediscovered by Columbia records in 1969 and then by Charles Amirkhanian in the 1970s, who popularized his experiments with hand-punched piano rolls for the player piano.

He once wrote a piano sonata for Ursula Oppens, although the middle movement was said to be “unplayable.” Thomas Adès performed that section in a San Francisco concert five years ago, and the following day demonstrated his technique to a roomful of pianists: by separating each hand into two sections, he could play the rhythms of two against three in his left hand and five against seven in his right. Maybe we could still call it unplayable!

He once wrote a piano sonata for Ursula Oppens, although the middle movement was said to be “unplayable.” Thomas Adès performed that section in a San Francisco concert five years ago, and the following day demonstrated his technique to a roomful of pianists: by separating each hand into two sections, he could play the rhythms of two against three in his left hand and five against seven in his right. Maybe we could still call it unplayable!

Nancarrow’s work is concise and dense, not unlike Alban Berg’s small and groundbreaking output, and is a result of the huge effort of transcribing written notation into a hand-punched score in order to achieve a complexity beyond human capability. But his works are gaining adherents. Besides influencing Adès and other composers, he has been the inspiration for the musical sculptures of Trimpin, a Seattle-based artist who this weekend mounted a large installation at the Berkeley Art Museum to honor Nancarrow as part of the centennial celebration.

Amirkhanian approached Cal Performances and the Berkeley Art Museum about a centennial celebration and the enthusiastic result was three days of colloquia, films and concerts, held at Hertz Hall on the UC campus and at the BAM.

Writing for the player piano is admittedly a narrow genre, but his journey was an odd one. After studying harmony with the young Roger Sessions and genre-defying music with Nicolas Slonimsky, Nancarrow joined the Communist Party and the Abraham Lincoln brigade to fight Franco and the Italian Fascists. (I have met members of the Lincoln brigade, still showing up for protests into their nineties.)

After escaping from Italy to France, he was imprisoned at the Gurs concentration camp. He returned to America in 1939, but, harassed as a communist, shortly after emigrated down to Mexico City, where he spent the rest of his life.

Last year I saw an installation and concert by Trimpin at Stanford, where he talked about growing up not far from the infamous Gurs, and his long journey to understand those War years, which included letters from the prisoners and his eventual discovery that Nancarrow had been held there (see May 18, 2011 Piedmont Post.) Trimpin journeyed to Mexico City in 1981 to copy Nancarrow’s pianola rolls, and has used electronic creations referencing those criss-crossing and subtle rhythms in his own musical sculptures. After speaking with David Frech, the computer mathematician who helped Trimpin design some of the work, I understood how closely Trimpin’s art built on Nancarrow’s.

At Sunday’s culminating concert we were treated to several aspects of Nancarrow’s private dedication to his art. After the advent of tape recorders, and well before computers, Nancarrow cut and taped together the magnetic tape of a percussion recording in order to create his own “re-composition.” That original tape was utterly dramatic, heard from across a divide of many years, and was surprisingly corporeal. Just like with Japanese Taiko, which it resembled, one could feel those complex attacks in the body.

Then Bay Area percussionist Chris Froh reprised “Piece for tape” on drums, arranged by Dominic Murcott, and one could even more clearly feel the vitality of Nancarrow’s vision. A high point of the concert, Froh delivered a joyous urgency.

British pianola player Rex Lawson pumped and fed the rolls for a duet with violinist Graeme Jennings in Toccata for Piano and Violin, a work that was so furiously obsessive it made the drums look docile.

Lawson remained onstage to bring Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring to mechanical life, transformed from orchestral to player piano. After hearing The Bad Plus do an awesome electric jazz interpretation of this seminal work on October 12, it was fresh in my ear, and I was surprised at how expressive the pianola. Particularly, one could hear how truly revolutionary Stravinsky’s rhythms, no doubt helping Nancarrow down his own path of “temporal dissonance.”

After intermission the Bugallo-Williams duo performed selected Nancarrow works that had been re-transcribed for four-hands piano from the original pianola rolls, a feat that left us agog. While the duo performed technical wizardry in bringing out the disjoint tempos, it was only in smaller gestures or slower moments that one could feel the presence of heart. That shy presence was the essence of the evening.

A comfortable walking blues in the left pair of hands and a confused treble voice distorted early blues like a carnival mirror. That and trickles of high notes over a blues scale reminded one of William Bolcom’s Ghost Rags— another tinkerer who uses popular music.

Moments of blues, ragtime and Bach chaconnes flickered through their set, but the loveliest was evocative of Albeniz, dredging the Spanish sun and the beauty of flamenco away from Spain’s treacherous past.

—Adam Broner

Photo of Conlon Nancarrow, courtesy of Charles Amirkhanian