A tip of the hat to Stravinsky

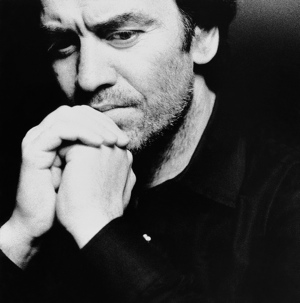

The New York Philharmonic held a three-week Igor Stravinsky festival this month, with eight different programs under the baton of Valery Gergiev, acclaimed general director of the Mariinsky Theatre and principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra.

It has been a high point of the Philharmonic’s season. And one of the high points of that festival was Oedipus Rex, arguably Stravinsky’s most popular neoclassical endeavor, and one of the twentieth century’s greatest oratorios.

I was in New York on Saturday, May 1, and was fortunate to get a ticket to this event. But I didn’t realize that Gergiev had arranged an historic triple threat. Behind the Philharmonic stood the renowned Mariinsky Theater Chorus—Russian basses and tenors who added sonorous vowels and edged consonants to the Latin text. Arranged in front of the orchestra were four soloists, among them Anthony Dean Griffey, a tenor who recently came to prominence as the Met’s tragic/evil Peter Grimes. Griffey sang the part of Oedipus Rex, and his was a boastful part deserving of the wrath of Gods. The spoken text was narrated by Jeremy Irons, a forceful actor who bespelled the audience and impelled the orchestra to a high pitch.

Stravinsky wanted an oratorio that was emotionally compelling but formal, and after engaging his friend, filmmaker Jean Cocteau, to write the libretto, he had it translated into Latin. Cocteau, however, insisted that the narrator speak in the prevailing language for each audience. And they were both right. The combination of Latin singing and direct description mirrored the piece itself, an ancient Greek legend with a contemporary emotional punch.

Along with Griffey was a memorable performance by Mikhail Petrenko, singing the bass parts of Creon and the Messenger.

Irons’ plummy voice was nostalgically upper crust. I was taken back to the days of Radio Theater. “A trap…that closes!” he intoned, and instantly the horns and chorus responded, discordant and hair-raisingly tight. I had forgotten how exquisite this horn section is, possibly the best in the world.

Stravinsky had earlier written The Firebird, Petrouchka, and The Rite of Spring for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, with roots in Russian folk scales and striking rhythms. Oedipus, written in 1927, belongs to his later “neoclassical” period, which relies on stricter diatonic scales and slimmed down orchestration, with more harp and winds. But the sharp rhythms, minor seconds and lower brass retained some of that earlier savagery, one that famously caused a riot in Paris. When trumpets and chorus join in strident unison on “Solvit! Solvit! Solvit!” one thinks of Balkan or ancient Greek choruses.

The edge of the seat music paved the way for Irons to steal the show, with pronouncements as terse as a politician’s. “This Oedipus… he is the only one who does not see. The Truth strikes… and he falls. He falls. All the way.”

The long program opened with Stravinsky’s 1946 Orpheus, a tone poem whose lines were unabashedly simple. A harp played luminous descending notes as Orpheus wept for Eurydice. The music, which begged to be coupled with its dance, stood on its own to reveal a lovely cello solo and half-hidden clarinet-harp textures.

For those in New York May 27-29, Alan Gilbert will conduct a rare treat—Ligeti’s only opera, the dark and surreal Le Grand Macabre. For more information, visit nyphil.org.

—Adam Broner

Photo of Valery Gergiev; photo credit Marco Borggreve/Decca