Soccer and Genocide

Santa Cruz’ Cabrillo Festival, held the first two weeks in August for the last 47 years, is an opportunity to revel in pioneering orchestral works. Their outstanding opening, Azul, was reviewed in the Aug. 19 Piedmont Post. The following day there were three thoughtful treatments. Spices, Perfumes, Toxins! (2006) by Avner Dorman explored a potpourri of middle-eastern and Indian rhythms and colors and flaunted the percussion talents of Festival regulars Steve Hearn and Galen Lemmon.

Brett Dean’s Moments of Bliss is a suite from an opera-in-progress with expressive moods augmented by sound tracks. In the first movement a jazz piano delivered smoky musings against the murmur of taped conversations through cheap motel walls. Muted trumpet snaked through to add sleaze.

And Enrico Chapela based his 2003 ínguesu on a famed 1999 soccer match between Mexico and Brazil. The soccer fans’ chants are well-known motifs, which Chapela incorporated.

And Enrico Chapela based his 2003 ínguesu on a famed 1999 soccer match between Mexico and Brazil. The soccer fans’ chants are well-known motifs, which Chapela incorporated.

At a composer’s forum earlier in the day, he was asked what ínguesu meant. He laughed and redirected the question, so one may assume it is colorful.

He also spoke of his difficulty breaking into composing. Without financial backing for an orchestra, he was still able to enter a competition by crafting a demo CD: he spent six months and 110 tracks and played many of the instruments in his “virtual” orchestra, winning the commission that allowed him to create ínguesu.

Replacing typical orchestral balance and color with a playbook, and a conductor with a referee, Chapela read out a list of the players: woodwinds were Mexico, brass, Brazil, strings were the chanting fans, and conductor Marin Alsop? She appeared to cheers in a black and white striped referee’s uniform with a whistle around her neck.

One was reminded that musical systems of organization are primarily vehicles for development and dramatic tension. Chapela’s cries and fouls can be as direct as Shostakovich or as nuanced as Debussy.

Woodwinds kicked the motifs around, then brass grabbed the lead, running with sharper cross-rhythms. After a furious development, Alsop blew her whistle and held up a yellow card, warning the trombones.

Marimba and cowbell added catcalls, and the brass came back in, heavy footed and working the field. Violas were sharply up-bowed, hoarse cries of the crowd, when the bass trombone abruptly re-entered, breaking rhythm and running with his solo. Alsop blew her whistle again and held up the red card, fouling him off the field.

Gesturing rudely, he got up and slouched over to the exit, where he turned and blatted an impertinent word.

Taunting and virile, this piece was infectious, and the audience was giddy with displaced patriotism.

Consummation at the Mission

Their final concert is held in the Mission of San Juan Bautista, a huge adobe structure with magical acoustics. Squat pillars supported the thick arched walls, which rose to carry square-hewn vigas. Lesser naves flanked the long central chamber, so waves of sound rolled up and down, thickened like the three strings near-tuned to each piano note to bracket and enrich the sound.

George Tsontakis created Claire de Lune (2007) as homage to Debussy, and within its off-kilter modernity older textures emerged—woodsy flutes and whole tone scales. The melodies blurred, mistimed for a softer focus.

Kevin Puts’ Two Mountain Scenes (2007) used a similar device, but more pointedly. Trumpets staggered their entrances, painting a mountain scape with echoes. Gentle tone poem gave way to high-country storm, with torrents of strings and winds blowing every which way. Notes swelled in their middle to evoke large forces and unpredictability. With eyes closed, one was easily transported to a Colorado mountain.

After the death of his brother-in-law in Yugoslavia, Ingram Marshall composed Kingdom Come as that country destroyed itself with civil war and “ethnic cleansing.”

Soft kettledrum and cello commenced a distant bombardment, then swelled as strings fluttered. Pairs of notes stepped down infinitely, a slow shimmer that returns at the end.

We became aware of an electronic element as bass notes emerged from the subsonic, and gradually distilled into voices. Marshall had earlier recorded Bosnian religious services—Croatian Catholic, Serbian Orthodox and Bosnian Muslim—and their sepulchral voices gathered substance in the aisles. The brass entered one by one until the church reverberated. They slowed, and, punctuated by electronic flutters, a muezzin’s high slides turned to grief.

Written in 1995, this requiem was a powerful rebuke to Serbian nationalism. But not powerful enough. Three years later Milosevic began another genocide in Kosovo.

—Adam Broner

This article originally appeared in the Piedmont Post.

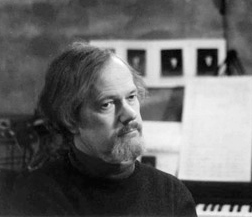

Photos: top, Enrico Chapela speaking before the performance, photo by Frank Hhler; bottom, Ingram Marshall, photo courtesy of the Cabrillo Festival.