A powerful work of literature was given new life last Saturday, Feb. 23, at San Francisco’s Z-space, a venue known for its experimental theater and its many premieres. Howard’s End, a page-turner by E. M. Forster, was repurposed as the opera Howard’s End, America by composer Allen Shearer and librettist Claudia Stevens, and it was skillfully done.

In the original story the lives of the wealthy Wilcoxes, the middle class Schlegels, and the poor Basts are twisted together by messy bonds, with love wrestling against class. Shearer and Stevens transitioned that central theme into opera, but re-focused the class wars of an older British generation into the class conflicts and racism of 1950s Boston, simply by casting the Basts as an African-American couple.

But this is also a story of redemption, of how the perceptive heart of protagonist Margaret Schlegel is able to connect with rich and poor alike. “…how love and compassion are what save us all from the abyss,” Stevens explained in an interview on their opera project website.

It is a chancy business to update great literature, and their success is pertinent to us: these are the roots of America’s present-day war on the poor.

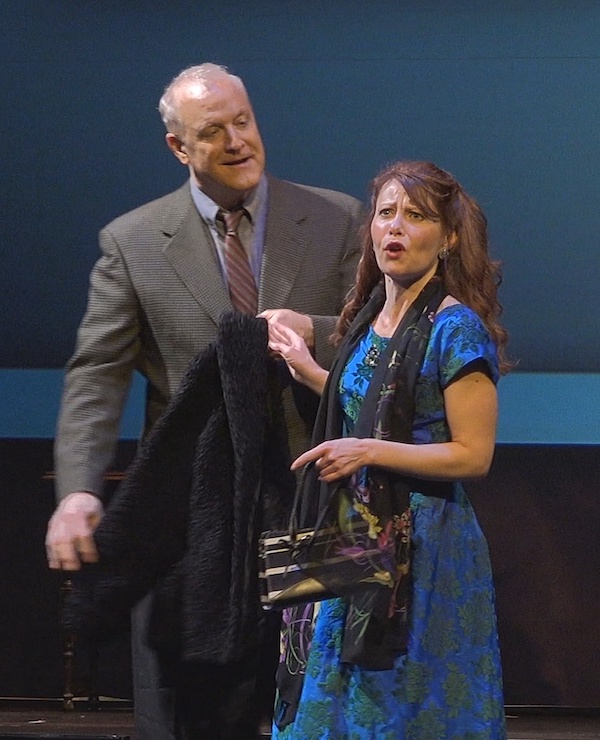

“It’s the passive and the doers, the winners and the losers,” sang bass-baritone Philip Skinner as industrialist Henry Wilcox, shedding his social responsibility like a cold shower.

“He is a good man, a good man, whatever his faults,” responded Nikki Einfeld as Margaret, apologizing for Wilcox. She has seen beneath his habits and fears into a place where we cannot help but love one another.

Stevens edited Forster’s round phrases into a language that was spare but filled with innuendo, nearly poetic in its simplicity. Complementing that, Shearer’s composing was rich in its many moods while remaining astringent in its modernity, edgy and atmospheric and all closely knit to the text.

The music was performed by thirteen musicians, members of the new music group Earplay and invited others, led by Earplay conductor Mary Chun. These were top musicians, as they would have to be for this, and I recognized them from several Bay Area ensembles. There was something colorful yet incomplete about that soundscape, with the instruments and sung voice traveling sometimes in parallel and sometimes forging their own terrain, and together creating dramatic tension.

Upward musical gestures opened the opera, imperative and anxious, and we intuited that it was about to rain even before the cast scurried onstage, heads bent under umbrellas.

Moods and forms flowed seamlessly, blurred between atonal, jazz and classical as the drama dictated, with passages of Beethoven and Fats Waller and Gershwin, quotes from e. e. cummings and Shakespeare.

A strong cast of seven excellent singers carried the narrative. Skinner and Einfeld are both well-known to Bay Area audiences, and there were moments when their acting was so convincing and their voices blended so richly, that they took us into the privacy of the moment.

The other couple was tenor Michael Dailey as aspiring poet Leonard Bast and soprano Sara Duchovnay as Helen, one of the two Schlegel sisters. Each was accomplished in their own arias and their duets were inspiring, bright soprano and yearning tenor, clean harmonies over a field of uncertainty.

As Jacky Bast, a former night club singer and Leonard’s wife, Candace Johnson sang Ain’t Misbehavin’ with lovely scoops and scats. And she personified her loose stereotype even while returning to contemporary intervals. Erin Neff embodied the gentle strength of the family house, Howards End, as Ruth Wilcox, and Daniel Cilli was perfect as the baritone everyone loved to hate.

The most striking moment, both musically and dramatically, was the birth aria, where Duchovnay delivered high arcs of wordless song and open-throated lows, cresting over her contractions as woodwinds arched along with her. The troughs were layered and translucent, low bowing in the strings like waves of sea-foam as the pain receded.

It was riveting and unique and moving, and, surprisingly, there is nothing like that scene in all of opera.

In their online interview Stevens and Shearer talked about writing that aria and also about the process of a married couple collaborating artistically. “Let’s make the labor pains musical,” Stevens had suggested. Shearer added, “Claudia was a big help there, and she has actually given birth twice, and knows what labor pains are like and how they are… timed.”

“The peaks and valleys,” she added.

“We’re very flexible,” said Shearer. “We do a lot of revising together… and I’ve found that she’s always right.” Stevens smiled at that, then added, “We really do put vanity aside. We are on the same page, literally, and it is a pleasure and joy.”

—Adam Broner

Photos from top: Sara Duchovney and Michael Dailey, photo by Jasmine Van T; Philip Skinner and Nikki Einfeld, photo by Jeremy Knight; and bottom, cast, photo by Jeremy Knight.