Modern treatment for Brahms—and for an old theater

Three vital modern works vied for space with an old Master last Thursday, June 3, in Mill Valley’s charming 145Throckmorten Theatre. The Bay Area-based Left Coast Chamber Ensemble performed living composers and Brahms.

A recent renovation maintained the character of the original dance hall and silent movie theater. But now burnished mahogany detailing embellishes walls painted with evening blues. Gods and goddesses cavort in the pink-tinged clouds, and trompe l’oeil boxes seat muses and harlequins.

A recent renovation maintained the character of the original dance hall and silent movie theater. But now burnished mahogany detailing embellishes walls painted with evening blues. Gods and goddesses cavort in the pink-tinged clouds, and trompe l’oeil boxes seat muses and harlequins.

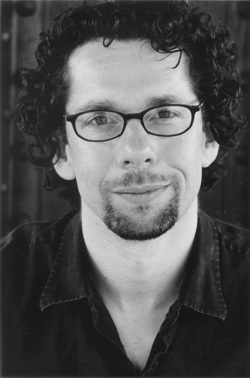

Curious threads ran through the night. Martin Bresnick’s trio for clarinet, viola and piano took as inspiration Brahms’ Trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano, which appeared on the second half of the program. Brahms wrote his trio in 1891, late in his life, and the complex trialogue overflowed with florid late-Romantic gestures.

Bresnick named his trio *** for a similarly titled work which Robert Schumann wrote as a love poem to his wife, Clara. Schumann’s dramatic language and Brahms’ subtlety transform in Bresnick’s modern hands to terse statements and arduous climbs.

“The three stars hide what it’s about… but indicate that it’s about something,” declared the composer in prefatory remarks. Rather than reveal his intent, Bresnick summed up with, “A composer should never speak longer than his piece,” to the audience’s mixed puzzlement and relief.

Clarinetist Jerome Simas opened with a soft note so high that when he dropped down to a second note one realized that the high sensation had pitch. Eric Zivian, once a composition student of Bresnick’s, entered with groups of five chords, creating structure. Clarinet and viola, played by Kurt Rohde, took turns arcing slowly down. A piano transition of stuttered chords led to new material that mimed time in reverse, a front-loaded language of clarinet vowels and viola fricatives. They worked back up the scale, climbing crabwise to end again on very high clarinet and a soft viola trill.

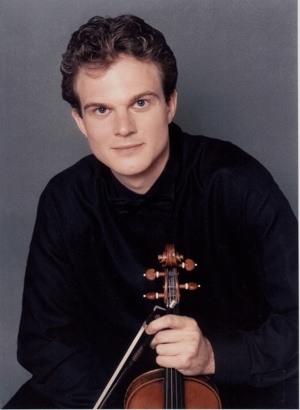

The three returned for the high point of the night, Kurt Rohde’s Concertino for Violin and Small Ensemble, dedicated to and featuring AxelStrauss, a gifted violinist and Bay Area treasure. Strauss’ 1845 Pressenda violin filled the hall with warm waves of sound, and its wielder was jaw dropping in Rohde’s fiendishly difficult passages.

The Concertino, composed in Rome during a year-long residency, is cast in three movements—moto, sotto, rotto (motion, under, broken)— and built on evolving intervals. Strauss opened with slow tritones and slides, and the ensemble answered with trilling intervals and the “tuning up” sounds of open strings. Double bass player Michael Taddei and flutist Stacey Pelinka, both regulars of the Berkeley Symphony, added jazz elements, and percussionist Loren Mach’s sudden clatter helped propel them down the stairs. In sotto Strauss revealed the heart of the piece, with slow double stops and a gracious quality. Then they threw caution to the winds in rotto. The violin’s furious sixteenths were reminiscent of John Adams’ energetic minimalism, and the rest fused Ligeti with a washing machine.

and built on evolving intervals. Strauss opened with slow tritones and slides, and the ensemble answered with trilling intervals and the “tuning up” sounds of open strings. Double bass player Michael Taddei and flutist Stacey Pelinka, both regulars of the Berkeley Symphony, added jazz elements, and percussionist Loren Mach’s sudden clatter helped propel them down the stairs. In sotto Strauss revealed the heart of the piece, with slow double stops and a gracious quality. Then they threw caution to the winds in rotto. The violin’s furious sixteenths were reminiscent of John Adams’ energetic minimalism, and the rest fused Ligeti with a washing machine.

Though the ending was abrupt, Concertina has enduring material and will no doubt find its place in the repertoire.

Pelinka and Mach opened the evening with Ariadne by Lou Harrison, a Bay Area composer who died in 2003. The improvisatory quality displayed Harrison’s quest to blend Eastern and Western virtues, and indeed he spent his life recreating gamelan and using just intonation in his compositions. The Greek subject lent itself to his hypnotic lines, with Pelinka’s intense low notes painting Ariadne’s mystery and allure.

Pelinka, noticeably in her second trimester, may have been a little breathier than usual. But her rich tone suited the old theater.

—Adam Broner

Photo, top: German-born violinist Axel Strauss, winner of the 1998 Naumberg Violin Prize and a Professor at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Photo, bottom: composer and violist Kurt Rohde, photo credit Frank Doering