A dream and a dream…

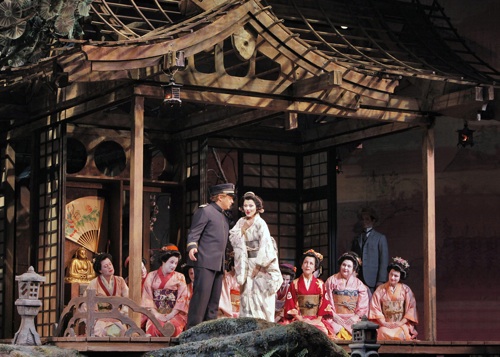

San Francisco Opera’s production of Madama Butterfly, by Giacomo Puccini, stressed the magical surrealism of dream Friday night. Director Jose Maria Condemi and set designer Clarke Dunham created a miniature realm of fragile tranquility and stylized movement. The backdrops represented nature as if from a painted silk shoji screen, while the hilltop cottage, rotated by black-clad and veiled figures, held the serenity and tradition of Japanese architecture, a mating of order and nature.

The scene was set socially as well, as those veiled figures of Kabuki Theater crouched or lay prone when they were not pulling the set with slow, T’ai Chi-like steps. Their objectification diminished the price of life, setting our stage for the crueler choices of love amid poverty. Two pillars flanked the set, arising from solid bases into gossamer trunks before gaining enough solidity to visually carry the top girder. A combination of magical lighting and transubstantiation into taut silk let us see through the pillars, layering reality into dream.

…and vision into nightmare.

But those sets only reflected the social milieu. The characters’ desires and expectations created a separate reality, as disjoint from each other as from their setting. While celebrating his nuptials with “bought” Japanese wife Cio-Cio-San, or Butterfly, Lieutenant Pinkerton toasts the consul with “…a flower in every port.”

Pinkerton was sung with feeling and acted convincingly by tenor Stefano Secco. His was an understandable villainy, the everyday thoughtlessness that propels much of the evil of this world.

Hawaiian baritone Quinn Kelsey, in the role of the Consul, answered Pinkerton’s toast with a caution: “That’s an easy code to live by, but it saddens the heart.”

Heedless, Pinkerton continues, “…and to the day when I have a real wedding with a real American wife.” Nagasaki was apparently a dream to him, peopled with gentle and mysterious denizens and his new child bride of 15 years.

“It were indeed sad pity to tear those dainty wings,” replied the Consul. Kelsey’s darkly textured bass grounded each scene that he was in, while his reactions doubled the impact of the others, cueing the audience to their emotional nuances. When he covered his eyes from grief at human blindness and fate, he assumed the mantle of a Greek chorus, a conduit for inevitability.

Opposite Pinkerton sang Rumanian soprano Svetla Vassileva, and her acting delicately portrayed the young Cio-Cio-San. Her dream, one of wedded bliss, was at odds with their wedding of convenience, and her heroic faith laid the groundwork for tragedy.

Butterfly’s character and dilemma is the focus of the opera, and Puccini works that role, from gravelly low notes to extreme highs. It is a rare voice that can essay that and also give it the clarity of youth. Vassileva worked hard to fill the space, using a broad vibrato to help project. Her love duet with Pinkerton was marred by that, as their large vibratos kept them from tighter harmonies.

And her grand moment, the second act aria “Un bel di” would have been more powerful had she been allowed to sing at half the volume. Indeed, her opening was gorgeous—and softly pure. But conductor Nicola Luisotti, who mostly led the SF Opera Orchestra with energy and care, apparently thought that it was his big moment: he swelled at her every crescendo, forcing her to muscle her voice over the top of the instruments.

Mezzo-soprano Daveda Karanas did a great job as Suzuki, Butterfly’s maid, with warm singing and perfect timing. She was neatly complemented by the unethical matchmaker, Goro, sung by local tenor Thomas Glenn. His clean lines and superbly dastardly acting reminded me of his role as The Snake last year in The Little Prince.

Puccini chose Japan, recently opened to the West, perhaps to suspend disbelief through a new and exotic setting. Within this fairy-tale world, the characters gained contrasting believability. Forty years earlier George Bizet set The Pearl Fishers in a bizarre quasi-Hindu fishing village, and we swallow his love triangle and tragedy whole in a suspension of everyday logic that is child-like and wondrous.

While some may decry the sexual imperialism at the root of the plot, each character is too deeply realized to stereotype. Puccini manages to allude to brash American expansionism and to the Japanese commodificaton of marriage without descending into political tract, but he does throw a few darts at patriotism and aesthetics. When Pinkerton appears, a trumpet fanfare derisively greets him with fragments of the American anthem, “ O! say can you see?” When he is gentled by love the anthem appears in the lower strings, and occasionally shifts into minor, a shadow of what is to come.

Cio-Cio-San’s motif is written in Asian pentatonic scale, but like her character, she employs a larger language. Their love duet is rooted in Japanese scales, while the orchestra is tender with chromatic passages. And “Un bel di,” Puccini’s version of “Somewhere, over the rainbow,” is a lovely blend of Italian aria and pentatonic minor, simple and emotionally direct.

This opera, the second most performed by the SF Opera, is deceptively deep. Under its social and political cross currents Puccini directs us to a complexity of character that mesmerizes us a century later: as Cio-Cio-San is wooing and being wooed, she feels a sudden fear of her choices, and sings to Pinkerton, “Ah, love me a little, oh, just a very little, as you would love a baby. We are a people accustomed to small things…to tenderness. Light and yet profound, as the sky, as the sea.”

—Adam Broner

Photo top, Rumanian soprano Svetla Vassileva sings the role of Cio-Cio-San in SF Opera’s current production of Madama Butterfly. Photo bottom, tenor Stefano Secco as Pinkerton with Vassileva and geishas; both photos by Cory Weaver. Originally published by the Piedmont Post.