Since the mid 20th-century and perhaps earlier, depending on the art form and how radical the practitioners, beauty as a feature of high art has been suspect. Beauty, it’s claimed and with reason, soothes and distracts, makes us accept the unfair and corrupt in our society and revel in the gorgeousness of art before all things. Beauty is easily duplicitous.

Certainly Triptych (Eyes of One on Another), which played at CalPerformances’ Zellerbach Auditorium this past weekend, brings that perspective in sharp focus. For one clear thing about the performance was that it endeavored to be beautiful.

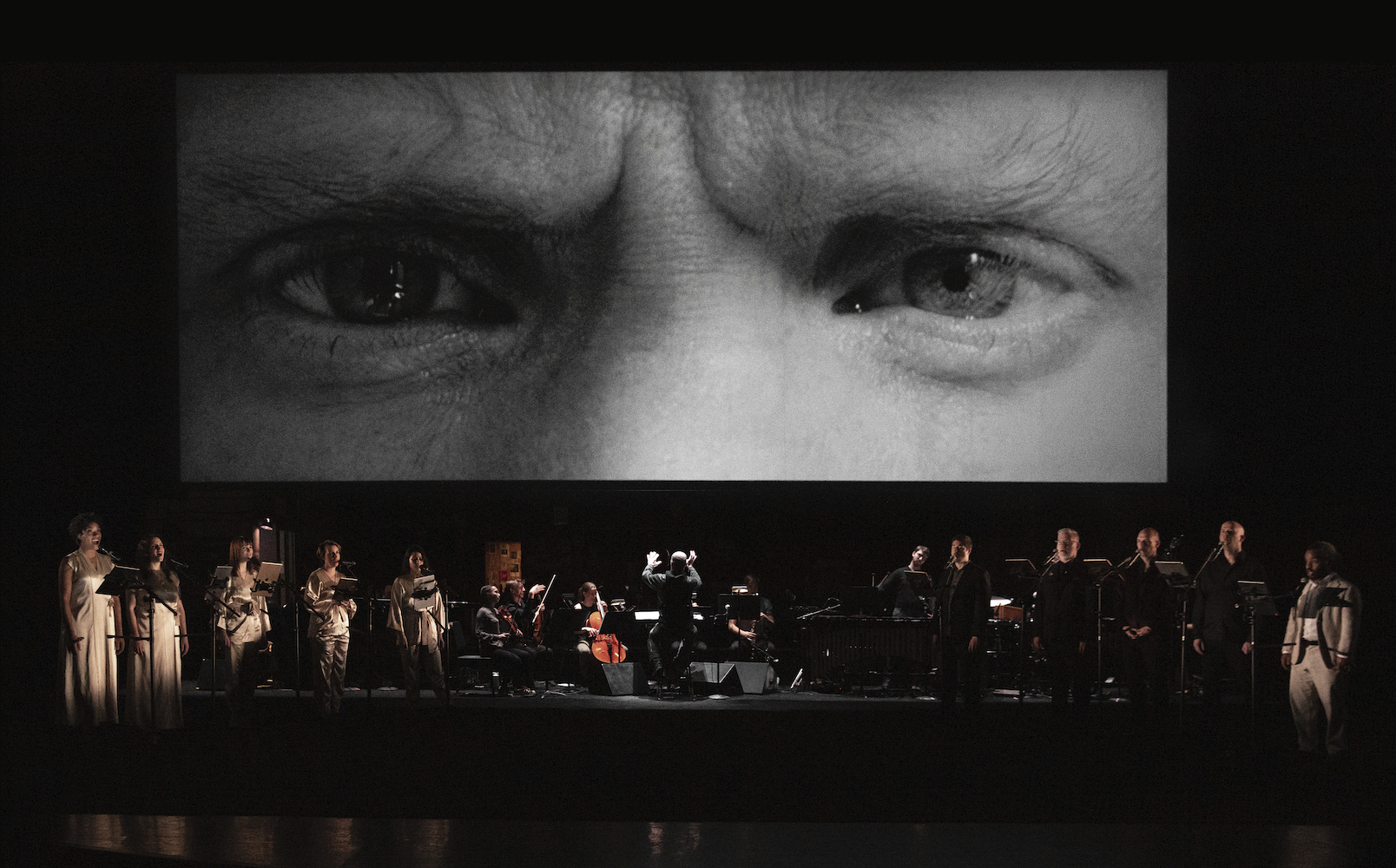

Led by the extraordinary vocal group Roomful of Teeth, though a more accurate name might by Roomful of Vocal C(h)ords, the multimedia, cross-genre production is an homage to the late photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. Singing a libretto by korde arrington tuttle set to music by Bryce Dessner, the eight-member vocal group performed on a mostly darkened stage, where instrumentalists from San Francisco Contemporary Music Players sat in a line across upstage.

The music ran a wide gamut, opening with Monteverdi’s Incenerite spoglie (Tears of the lover at the tomb of the beloved) with its exquisite elegiac tones through edgy settings of Patti Smith to more robust gospel settings of Essex Hemphill’s poetry. Throughout there were dazzling harmonies, exotic vocal techniques and mind-boggling solos. Alicia Hall Moran and Isaiah Robinson were heartbreaking in the wonder of their vocal solos.

The libretto was projected onto scrims, intersecting with Mapplethorpe’s photographs, a necessity since vocalization alone would have been impossible to decipher. The text was tastefully set in a sans serif.

The 60-minute piece was divided into three section, designated X, Y and Z. The section names were taken from the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center’s show of Mapplethorpe’s work, The Perfect Moment, which later became the focus of an obscenity trial in 1990. The portfolios were comprised of gay S&M (X), flowers (Y) and nude portraits of African-American men (Z), but the subjects of the performance photographs were not so restrictive, each infiltrated the other. And in the second section images from the obscenity trial documents were included.

The images were projected on various scrims, either in front of or behind the singers. Often two images divided the screen in half horizontally, the strong black and whites of the images creating a clear divide that had its own designer urbanity. The luscious videography was done by Simon Harding with Moe Shahrooz as the associate video designer.

And here we get into the problem of beauty.

There is something glossy about Mapplethorpe’s images. His attachment to formalism and perfection within formal terms, further exaggerated by the tonalities of black and white, often give his photographs a Vogue magazine quality. Oh yes, beautiful, but somehow too studied. His concept of perfection is as clean and white as a new refrigerator. And some of the images are frankly banal in their reach for the dark and disturbing. Take for example his self-portrait with the skull-headed cane, or the photo of a man with an erection holding a gun, both pointing in the same direction.

The photographs were helped by the stage-high projections that softened the line and made the blacks and whites into shadows and open areas of light. Even so, objects and objectification run strong in the artist’s oeuvre.

Many of the photos in the third section, comprised mostly of photographs of African-American men (and one woman, whose Nefertiti-like profile appeared over and over, multiplying her solitary presence), were published by Mapplethorpe in The Black Book, which was received with anger by Essex Hemphill, who pointed out that Mapplethorpe’s “much-celebrated technique, his ability to photograph (black) bodies as if they were marble or bronze sculptures, actually continues a centuries-long tradition of separating black physicality from black subjectivity.”

And while the artistic team can say that they have covered this by including Hemphill’s poetry, especially “The Perfect Moment,” which was dedicated to Mapplethorpe as a criticism, the music and the generally elegant design of the production undercut Hemphill’s intent, so that the poem became just another set of interesting and beautiful words in a stylish production.

The statements made by the contributing artists that they were presenting a variety of ways to look at Mapplethorpe generally rings hollow because of that.

—Jaime Robles

.