The voice of autism …

Much has been heard about autism in the past 20 years or so. Presumably because of the rise of the condition: 30 years ago the incidence was one in 1,000, now it’s one in 68. Whether that’s a result of increased reporting, genetics, increased environmental pollution, undiscovered factors, or some combination of those is unknown.

In any event, the problem is there, needing to be addressed. Nancy Carlin and Michael Rasbury’s Max Understood looks at autism through the medium of theater, more specifically, musical theater. The play’s world premiere ran last week at Fort Mason’s Cowell Theater, produced by the Paul Dresher Ensemble.

Sound is the driving force behind the production, just as sound is a driving force in the world of the autistic child, who often suffers from an almost excruciating sensitivity to physical sensations. While most of us can turn off everyday sounds with some success, the autistic child may not have that capability. The churning of a washing machine can be unbearable. A passing siren in the street an assault. And the incessant chatter of the television insinuates as a monster, becoming the obsessive master of the child’s uncontrollable impulses.

When the play opens the adolescent Max, acted by the extraordinary Jonah Broscow, is standing in a cranny of the slanted turntable of a stage that is centered on the main stage. The noises he makes in response to the domestic sounds that surround him reveal his distress: he whimpers, hums, and whines to the increasing cacophony. Then the noise moves into his body and he begins to shake.

His parents appear, played by Teddy Spence and Elise Youssef, and like most parents their attention and their lives are centered on their child. Problem is their child does not respond in turn. He’s lost in some alternate universe of sound and light, advertising jingles and detailed facts about the presidents of the United States and who knows what else. In a long fraught duet, his parents pose each other and Max the ultimate question: Why can’t we be normal?

The difficulty of this first half of the play is that the audience has to undergo the distress the family suffers, brought on by Max’s unpredictable behavior and his parents’ frustrated reactions. It’s not easy to watch. The difficulty with the play in those moments is that we remain outside Max, captured by the anger and unhappiness of his parents. As long as we are engaged in the question of normalcy we have no way into Max’s experience and consequently no way to feel sympathy for him. Theatrical catharsis is blocked. And the mystery of life in its shared complexity is somehow submerged.

… speaking out

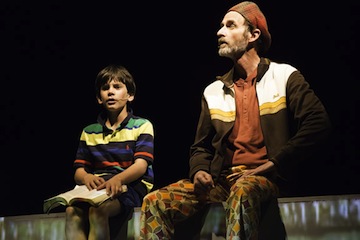

This challenge to one’s empathy is lessened when Max escapes from the house. He runs into a motley cast of characters: a maintenance guy named Munc (Jackson Davis) and three adolescents, Fin (Alyssa Rhoney), Albert (Jeremy Kahn) and Peg (Hayley Lovgren). Together they continue Max’s parents’ grievance. It is only when Max meets them separately as individuals that everyone is transformed and we have a glimpse into the near preternatural world of Max’s imaginings. And in those encounters the block between us and Max softens and dissolves.

All four characters are, like Max, marginal to normalcy. But each of them appear to him as a listener and a source. Munc becomes the poet philosopher. Albert is the geeky dumpster diver (as Fin says to him, “haven’t you got a Harry Potter conference to go to?”) who is likely to be on the same spectrum as Max. Peg, the chubby girl hanging out the laundry, becomes Pegasus the winged horse. And Fin becomes a mermaid, “air is water with holes in it,” she tells Max. Max, in these meetings, is revealed and, for the onlooker, enters a world of mystery, imaginative and uplifting.

The sound design by The Norman Conquest enhances Rasbury’s music, and was intelligent and innovative in its realization. But what was missing from the palette was acoustic sound. Everyone was on mic, as is the unfortunate practice for theater music. And the music was all electronic with Music Director Jennifer Reason directing the singers while seated in front of playerless equipment. I longed for at least one instrument or one voice without the medium of a speaker.

Although the musical’s run is complete, the newly invented and constructed instruments in the accompanying installation, Sound Maze for Max, continues at Fort Mason until May 3. These are definitely worth a visit to The Firehouse. The ten instruments, some of which you can climb up on, are available to play with. Ping pong balls sway back and forth on wooden boxes, metal hoops spin on hollow floors, a huge music box reel of magnetic stops booms out of enormous organ piles. The instruments were collaboratively designed and built by Paul Dresher, Alex Vittum and Daniel Schmidt. The installation is free.

– Jaime Robles

Photo: Max (Jonah Broscow) and Munc (Jackson Davis) discuss the world of poetic devices. Photo by Mark Palmer.