Mixed salad at Paramount

The Oakland East Bay Symphony played to an indulgent audience last Friday, January 28, with a surprising combination of nationalistic Armenian works and Brahms’ powerful and subtle German Requiem.

But the success of that “odd couple” program rested on two strands: harmonic and vocal. In Avetis Berberyan’s three pieces, the simple major modes and folk motifs showed off the golden colors of the Oakland Symphony, with dizzying horns and cymbal bling. But the Requiem held a different power, from subtle harmonic progressions to stern minor thunder. The other strand was vocal, with soprano and tenor soloists in the Berberyan and with soprano and baritone soloists in the Brahms.

There the similarities ended, but the variety of vocal material made for fascinating differences. Armenian pop singer Ani Christy, an award-winning 25-year-old sensation in Yerevan, delivered the lyrics, from maudlin to heroic, with all the charm of popular song. She used the mike to amplify the entirety of her process, from husky breaths to drizzled vowels. In “My Mother” she sang across the Oakland Symphony Chorus, which vocalized “Ahs” in a beautiful descant.

In “Wake Up, Armenian,” her careful diction was matched by operatic tenor Thomas Glenn, whose pure Italianate vowels and vocal power were st

unning—but clashed with Christy’s folk/pop traditions.

Conductor Michael Morgan kept the troops en pointe throughout, from the churchly invocation of tubular bells to big Disney-like moments. In The Hero’s Journey—Suite, strings created a simple, heartfelt wrap in the first movement Adagio. Then snare drum and clack of sticks gave Battle its martial mood, with trombones and French horns sketching a lonely wandering line.

It was stirring stuff, and the audience lapped it

up.

After intermission, Morgan trotted out the master. And in his brief introduction Brahms did not disappoint, with delicate bass whispers, then cello murmurs and, finally, violin motifs to embrace the feathery choral entrance.

Brahms used an arsenal of developmental tricks, from lovely oboe moments to energetic brass. And the soloists were fabulous.

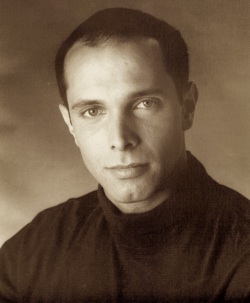

Brian Leerhuber brought a richly adorned baritone sound to the Requiem’s bass solos. His is a particularly German vocal type like Fischer-Dieskau, rather than a heavier bass, though he had plenty of carrying power while maintaining an intimacy of sound.

Soprano soloist Carrie Hennessey gave us Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit with a gentle luminescence that shivered the air—and without amplification. Her clarity was uplifting as she sang of a joy beyond death.

But the support and core of the piece—the Oakland Symphony chorus—was disappointing.

Though last year’s chorus was stellar in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, the vagaries of unpaid choristers gave rise to an insurmountable problem: there were too few men. The scant tenor section was helped out by low-voiced altos. But not helped enough. And the bass section—well, Brahms is all about the basses. (And timpani.) The basses make or break this sternly joyous work. When deep voices intone, “Denn alles Fleisch es ist wie Grass…” (For all flesh is like the grass) your neck hair is supposed to stand straight up. Instead we got a lot of middle register muddle.

Adding to that, the sopranos were sometimes wobbly, with pitch problems exacerbated by wide vibratos. All their hard work and tight fugues could not overcome the balance problems. And thus an event that should have been electrifying was only ho-hum.

The next performance, Friday Feb. 25 at 8:00, features violin virtuoso Regina Carter in a World premiere by jazz composer Billy Childs, along with Holst’s The Planets, a program promising to be memorable.

—Adam Broner

Originally published in the Piedmont Post. Photo top: pop vocalist Ani Christy brought life to folk spectacle. Photos bottom: soprano Carrie Hennessey and baritone Brian Leerhuber were soloists in Brahms’ Requiem.