Ambitious program at the Paramount

Two difficult and seldom-performed works made for an exciting program at Oakland’s Paramount Theater last Friday, Jan. 23, where Michael Morgan led the Oakland East Bay Symphony in George Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F Major and Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 8. These two works are so different that it would be surprising to find any points of parallel, but the two worked marvelously together.

But before they began, Morgan took the mike to announce the retirement of their beloved French horn player, Stuart Gronningen. Several fellow horn players spoke of how he helped shape their sound over the decades. He accepted presents and then buckled down for the night’s concert. What a pro!

Writing between the World Wars, Gershwin reflected an era that was artistically adventurous and alive with a rising social consciousness. Already accomplished as a songwriter and tuning his ear more and more to Tin Pan Alley and the burgeoning American jazz idioms, he exploded into the mainstream with Rhapsody in Blue, America’s answer to Euro-centrism.

Writing between the World Wars, Gershwin reflected an era that was artistically adventurous and alive with a rising social consciousness. Already accomplished as a songwriter and tuning his ear more and more to Tin Pan Alley and the burgeoning American jazz idioms, he exploded into the mainstream with Rhapsody in Blue, America’s answer to Euro-centrism.

His Piano Concerto was written over the next two years, again drawing on popular sources. One can hear the Charleston and blues and ragtime along with Ravel and Debussy in its busy dances, melting lyricism, and snappy piano cadenzas.

When Richard Glazier was nine years old he saw the movie based on the musical Funny Face, and was so moved by Gershwin’s songs that he wrote to Ira Gershwin, George’s collaborator and still-living older brother. They began a three-year correspondence. When he was twelve Ira flew Glazier out to hear him play the piano, after which he decided to dedicate his life to that era.

Now both a Steinway Artist and Gershwin scholar, Glazier turned in a performance that was utterly solid, and the symphony framed him with tight bursts of sound and their own languorous solos.

Glazier was a pianist’s “triple threat:” powerful, liquid, and sassy. While his iron fingers easily winged notes over the orchestra, his cadenzas were shockingly fast and smooth, turning diamond-etched notes into licks of fire. And beyond that, everything he touched had a visceral lilt, putting the oomph into the jazz.

This is a tough piece: besides the virtuosic writing for piano, it requires lots of expressive solos around the orchestra. The Oakland Symphony delivered. Opening the piece, Tyler Mack beat the timpani with the abandon of a Taiko master, then took it up-beat into a Charleston. William Harvey spiced up the middle movement with muted trumpet that was silvered with longing and then removed the mute for a gloriously golden development. He alternated with oboist Andrea Plesnarski, whose notes twined with trumpet for a magical chiaroscuro effect.

Morgan tried to prepare us for the difficult second piece. “When Shostakovich was writing this, WWII was almost over. But bear in mind that if they lost the war they’d have Hitler and if they won the war they had Stalin.” (nervous audience laughter) “It’s in C Minor but returns to C Major at the end. This is not a triumphant return, but a return to normalcy.”

The piece was long and disturbing, a severe meditation on a state of terror. While the Russian State may have claimed this was about the gravity of war, it became clear that Shostakovich might have been writing about a government at war with its own people.

Here we heard the same half steps that Gershwin so gloried in. But where George’s small intervals were nudging and sly, a swan dip on the dance floor, Dmitri’s minor seconds were obsessive/depressive, a stuttering uncertainty and fear.

This was brutal stuff, gloriously performed. Long naked build-ups, huge brass volleys and punishing piccolo solos (wonderfully executed by Amy Likar) framed an oppressive world. But between the bombast and the drear, one could hear Shostakovich’s veiled sarcasms. As dangerous as it was to say anything in Stalinist Russia, he went even further and used the final movement to “damn with faint praise,” a move that caused this work to be banned until 1956.

This was brutal stuff, gloriously performed. Long naked build-ups, huge brass volleys and punishing piccolo solos (wonderfully executed by Amy Likar) framed an oppressive world. But between the bombast and the drear, one could hear Shostakovich’s veiled sarcasms. As dangerous as it was to say anything in Stalinist Russia, he went even further and used the final movement to “damn with faint praise,” a move that caused this work to be banned until 1956.

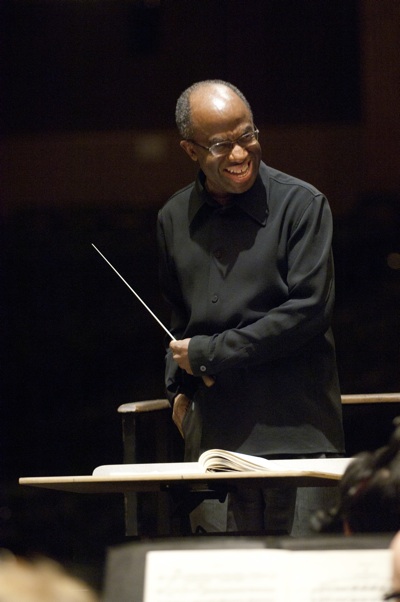

Afterwards, Morgan went through the orchestra gesturing various instruments to stand until every one of them was on their feet. These soloists were excellent and the sections were remarkably tight. Conductors often list this hour-long work as one of the truly great symphonies, though audiences are less apt to agree. Looking at the shining eyes of the musicians, I realized that they knew they had been part of something momentous.

—Adam Broner

Photo, top, of Richard Glazier, photo courtesy the OEBS; below, conductor Michael Morgan, photo by Pat Johnson.