Sailing into the Past

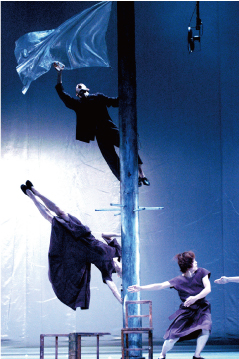

Out of 12 dancers in Japan’s Pappa Tarahumara dance-theater group, seven danced in Ship in a View when the work debuted in 1997 in Tokyo. Director Hiroshi Kioke has worked with one of his dancers for 27 years, most for at least a decade. Such longevity in dance troupes is not unusual, and it’s a requisite for choreography—like Kioke’s—that is complex and demanding.

The question it brings up, however, is: Pappa Tarahumara, where have you been all our years?

This past weekend the company brought Ship in a View, at last, to Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, and with it a glimpse into the company’s evocative and enigmatic form of dance.

Ship in a View is a work of nostalgia: Koike’s memory of the seaside town where he grew up in the 1960s. Although there are short narrative actions within the work—a woman seduces a man in a bar, a man dances with headless puppet, children sit at their desks in class—the work remembers movement before events. A little kid’s mouth drops open in amazement, a group of dancers cluster like a school of fish and their arms repeatedly make half of a swimming stroke.

Gestures even though recurring are always incomplete so that what the work presents is fragments, and, as such, the movements become metaphoric and therefore shaded in nuance.

Anchored Offshore

The troupe and even the choreographer’s vision have a distinctly Japanese flavor. Ship in a View reminded me of Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore. The author builds an absurdist story of conversational cats, soldiers who walk into a forest to disappear in this world and become the sentries to a mysterious “other” world, a self-declared “concept” that turns itself into Colonel Saunders of Southern-fried chicken fame, and an old man who can make it rain fish and leeches. Within those surrealist pages, the author constantly points out parallels between events in our more mundane world that are metaphoric: the labyrinth, one character tells us, is based on the idea of the intestine winding in on itself. What that may mean is only partly explained; we as readers make of this connection what we may.

A similar relationship with the audience is developed in Koike’s work.

The choreography moves at the pace of Noh theater. Whether a lunge into a martial arts pose or a jeté, everything proceeds slowly, deliberately. The work’s glacial gait is eased by the choreographer’s sense of the comic, anchored as it is in whimsy and a droll playfulness. Both qualities are well suited to some of the smaller dancers’ round, doll-like muscularity.

Throughout the work the dancers sing a series of strange textless songs as if they were ships calling through fog, hallooing to unseen listeners in an unearthly and haunting song.

The end of Ship in a View evolves into moments of spellbinding beauty. Most of the dancers leave the stage, which is dark and littered here and there with chairs. A grid of lights clicks on in the upper recesses of the stage. A woman, one of the two remaining dancers onstage, lies down on a suspended platform that is shaped like a human body. As she lies perfectly still, the platform moves starward; at the same time, the lights move earthward. They pass each other in slow and silent transit. The vision is breathtaking.

—Jaime Robles

Originally published in the Piedmont Post