Riffs on a theme

Emboldened by the success of last year’s Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, which involved massive editing and multiple media, Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony embarked on a similar voyage this week. Their point of departure was Peer Gynt, a four-hour long collaboration by playwright Henryk Ibsen and composer Edvard Grieg.

Inspired by this strange tale of an anti-hero seeking resolution, and ultimately, forgiveness, Russian composer Alfred Schnittke also wrote a score for a ballet version of Peer Gynt in 1985.

MTT’s attempt to unify those two versions into a single concert-length work, along with the “Ocean Voyage” segment from English composer Robin Holloway’s Gynt, was daring and mostly successful. Interleaving the coloristic sounds of Grieg with the penumbral timbres of Schnittke worked dramatically, even though these “apples and oranges” composers had few points of tangency. And to achieve even this they had to cut deeply from their two long treatments.

The resulting stew was necessarily telegraphic, turning Ibsen’s spare language stark. That spiky quality, compounded by the electronic amplification of the spoken text, was jarring in the resonant acoustics of Davies Symphony Hall, where a forest of curved Plexiglas sheets reflect the sound from the stage. Designed for sung and instrumental, the natural shape of Davies falls short with spoken word, of which there was a lot, necessitating the heavy miking of actors.

Despite all of this, the synthesis stitched together nicely.

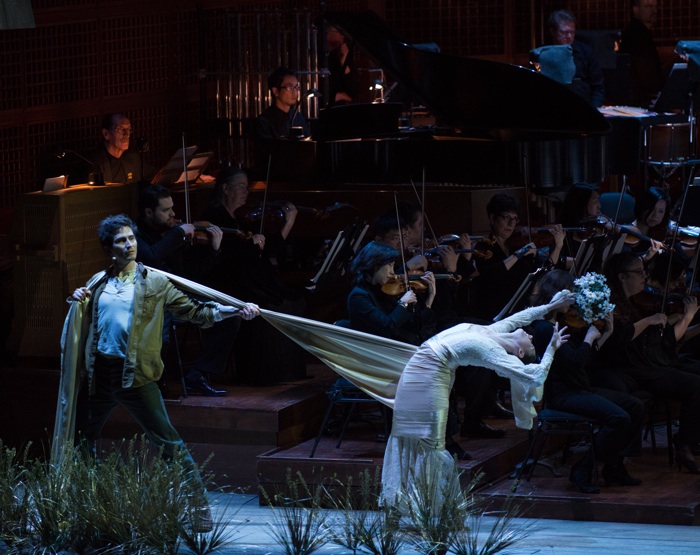

Though the story line was enchanting (even when it was revolting!) there were several moments that were completely over-the-top. The love scene between Peer Gynt, acted by Ben Huber, and The Woman in Green, performed by Peabody Southwell, conveyed shocking intimacy. Choreographed to the well-known strands of “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” there was something about the harrumphing bassoons, accelerating violin pizzicatos, and urgent score that added to their passion. I don’t know whether the music helped to create that very personal space, or whether it translated universal truths, but there sure was a lot of brow mopping in the audience!

And the other high point was the silken voice of soprano Joélle Harvey, who stopped the clock in each of her arias. Portraying the innocence of Solveig, her effortless octaves and poise led to a believable culmination, with a stern Northern morality finally displaced by forgiveness.

Musically, the Symphony was at its most robust, convincing and atmospheric in the Schnittke passages, with entrances full of metallic slithers and thrum of gongs, and then building into Shostakovich quotes and a freewheeling “polystylism.”

Holloway’s long “Ocean Voyage,” by contrast, was the most sustained musical concept, immersing us in his language. But that language, while full of the shifting sonorities of the sea, was less interesting than the other two composers.

Sustaining the themes—a search for identity in which the music certainly partook—director James Darrah and video designer Adam Larsen wove a believable cloth. Early in the work Huber uncoiled from the stage and turned to face the orchestra, with his own image video-projected onto torn scrims. As the man and the image moved towards and away from each other, I was tricked into thinking they were reflections, until they turned and went their separate ways. That search for identity, though at the core of Ibsen’s story, was somehow less relevant than Grieg’s immortal themes.

One hopes that the SF Symphony continues to create such thoughtful programming, bringing us works that would otherwise be unwieldy to stage.

—Adam Broner

Photos: top, actor Ben Huber as Peer Gynt, photo by Bjorn B.; soprano Joelle Harvey, photo by Claire McAdams. Bottom, Ben Huber and dancer Janice Lancaster Larsen as Ingrid, with the SF Symphony, January 17, 2013; photo by Kristen Loken.