Of cherry blossoms and nonsense songs…

Robert Commanday, one of the Bay Area’s more beloved music critics, passed away last Thursday, Sept. 3. A font of wisdom and wit, he was a reviewer for the SF Chronicle for three decades and the founder of San Francisco Classical Voice, an influential online magazine.

You can find tributes to him in several obituaries, but it seems appropriate to add one story that I find extraordinary. In the summer of 1957, twelve years after the end of World War II, Commanday took 50 young male singers to Japan for a month-long tour.

My father-in-law, Erwin Frech Jr., was one of those choristers. As a 22-year-old electrical engineering student, he sang in the UC Glee Club under the direction of a spirited 35-year-old Commanday. I visited with Frech this past Sunday at his 80th birthday party, and he was happy to share his memories.

But first he sang “Amo, Amas,” a nonsense song that Bob taught him, and that he sang to his young daughter.

I knew that he wasn’t doing well. I just saw him on Monday at a luncheon and a reunion of the Glee Club. We all knew that, and we moved up the reunion. Commanday was on oxygen, but he stood up and started singing a Cal Song, “Hail to California,” and we all sang. And then he spoke and said how wonderful we were as students. He used to call us “his boys.” One table began a medley of five or six songs and we joined in. These were songs we sang on that tour all over Japan, and at rallies and football games.

It was obviously difficult for him to breathe. I think he was hanging on until that luncheon.

I was in awe of Bob. I hardly spoke to him back when I was in the Glee Club in 1957.

I think he was in the Army [he was], and then went to the Army language school in Monterey and studied Japanese. I don’t know if it was because of what happened in the War, but he had a passion for Japan. He had this idea for a chorus trip that would be an outreach from our Western culture to their own culture, and he envisioned this whole thing.

He sent many letters to the Japanese Consulate and at first they brushed him off. But finally a connection was made and they started to talk and develop this thing. And they worked and worked to get a sponsor from Japan and finally got the Mainichi Newspaper Company, which was the biggest newspaper chain in Japan. They took care of everything and provided the guides.

Bob also spoke with Standard Oil and they also came up with a grant… and we had to raise a lot of the money ourselves.

Pan Am gave us a charter plane. It was a DC4, a four-engine prop, and the flight time from SF to Honolulu was 12 hours, at an elevation of 4000 feet! We stayed over for a day – the crew rules were a 24-hour layover. And then Wake Island, and another stay-over, and the beaches were fine but you couldn’t go into the jungle because of the old military ordnance, and finally on to Japan.

While we were there on Wake Island he taught us our first Japanese songs. Well, we already knew “Sakura” (cherry blossoms), but this was a very emotional thing for him because we were standing in a former Japanese Army Base on the threshold of Tokyo and learning Japanese songs.

And so we did that and we landed in Tokyo, at the Haneda International Airport. The place was packed with people! And there was a red carpet and flowers and singing, and we had no idea that all of this was going to happen… and it was like this everywhere!

At that time the Japanese were wide open to all of that: in Japan you’d go into a department store and you’d hear Beethoven and Bach. And singing was all the rage. Every town and company had a chorus, and schools had choruses. Everybody was singing, and they were multi-part choruses and they were singing not only their own music, but also ours. And they were hungry to hear English-speaking peoples singing Western music.

So when we arrived there we were treated like royalty everywhere we went.

Our concerts in Tokyo were all televised, and I think the Mainichi Company had a TV station. We were in Tokyo for three or four days and did multiple concerts. We stayed in a really nice hotel, in an isolated spot. It used to be some rich person’s palace and was converted into a hotel, and we would stay up all night drinking sake. I was 22, old enough! And some of the guys would try to out-drink the bartender. It was an informal kind of thing.

Bob would do the introductions to the concerts in Japanese. And everyone was very polite – too polite to laugh – but there would be a murmur.

The first half of the concert was classical, and then we would change out of our tuxes and into blue seersucker suits. And we would do the second half with folk songs, like “Down in the Valley” and “Poor Wayfaring Stranger,” and folk songs from Hungary and Spain. One that we enjoyed was “Tobacco was a Dirty Weed.” And during the intermission the Octet would come out and do their thing. They were the comic element of the concert, but I don’t know how that went over because their songs were so idiomatic.

Commanday was an outstanding conductor. Just outstanding. He taught us not only how he was going to conduct and how to respond, but he taught us how to sing – where to place your voice and how to shape your head. He was a trainer and a good conductor and the most important thing that we learned from him was to watch him. And the only way to do that was to memorize the music, and so that’s what we did. Our entire repertoire was from memory – there were only two people with books, the accompanist and the conductor.

Commanday was an outstanding conductor. Just outstanding. He taught us not only how he was going to conduct and how to respond, but he taught us how to sing – where to place your voice and how to shape your head. He was a trainer and a good conductor and the most important thing that we learned from him was to watch him. And the only way to do that was to memorize the music, and so that’s what we did. Our entire repertoire was from memory – there were only two people with books, the accompanist and the conductor.

I don’t know how many concerts we did in that month. At least twenty. Commanday cautioned us against singing outside of the choir rehearsals, because you can tire or ruin your voice. And we always had hot green tea at intermissions to relax our throats.

After Tokyo, we took the train south all the way to Shimonoseki. But first we stayed in a small town below Mount Fuji. When we arrived there were a gazillion people. We got off the train and a chorus from the village formed and they started singing, and that happened everywhere. And so we had to be prepared to respond in kind and we would sing something.

This was our first exposure to an old-style inn, where the maids would come in and prepare the room, and then they would try to help us undress. We were pretty shocked. And the restrooms were shared!

We continued south to Osaka, a very Western city, and to Kyoto, the cultural center of Japan where all of the main temples are. It’s very beautiful. And then Kobe, and then from Kyushu to Honshu through a tunnel, and we sang at an American Airbase there.

On our way back we sang in Hiroshima. The area that we were in was the center of the area where the bomb went off, and it was basically left the way it was, just bare and the trees all stunted. This was our smallest audience, and that’s not surprising. Our other concerts were standing room only.

We went back and toured in the northern region, which was getting cold. All of this took a month, and I don’t know where the time went. We had to hang out for an extra four days in Tokyo because our charter plane had damaged its landing gear. But they gave us a top-of-the-line Boeing plane that flew at 20,000 feet and at 300 miles an hour [three times as fast as the DC4].

The generosity of the Japanese was so unexpected. While we were waiting for those four days Mainichi gave us one last gift: for us all to have kimonos tailored. We all went down to this department store and we picked out the material and they measured us all up and had it done the next day. They were made by hand in one night!

Commanday was a remarkable conductor. And teacher.

Frech went on to describe how Commanday sent his singers into Letterman Army Hospital to sing Christmas carols to wounded American veterans, and I began to understand his vision: working to heal the scars of war through singing.

—Adam Broner

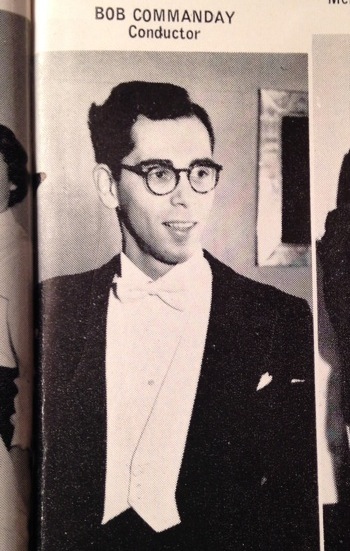

Photo top of Robert Commanday from the 1957 UC Berkeley Yearbook. Photo below of Erwin Frech Jr. and his great-granddaughter during this interview; photo by A. Broner.