On February 13, San Francisco Ballet premiered its latest collaboration with Trey McIntyre, The Big Hunger. In the program notes, McIntyre explains the concepts behind the ballet, which he set on the company this past summer. It’s based on the beliefs of the Kalahari Bushmen as described in the Korean film, Burning. The Bushmen claim there are two hungers in life: the small hungers that drive our everyday existence and the big hunger that is our longing for existential meaning. It’s the latter McIntyre hopes to address in this ballet.

It’s a big theme, but McIntyre seems to prefer them, as was seen inYour Flesh Shall Be A Great Poem, which premiered in SFB’s Unbound series two years ago and portrayed his grandfather’s dementia and death by traveling through moments of his youth and age in a symbolic yet tender homage to human vulnerability. There is always something gorgeous in the imagery chosen to represent the yearning conveyed by dancers through McIntyre’s choreography.

The Big Hunger deals with our existential longing on a large scale and in a symbolic manner, but the tone is markedly different from the previous ballet. That’s partly because the intimate connection between the choreographer and the topic is missing and partly because the music the ballet is set to.

An early work of the composer Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 2 (Op. 16) is a fiercely virtuosic work, one of the pieces that gave the composer his early reputation as an eccentric and challenging iconoclastic musician. To ensure an excellent performance of the piano part SFB brought in Yekwon Sunwoo, the winner of the Fifteenth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2017. And Sunwoo wailed on that keyboard Thursday night in a fantastic performance of the concerto.

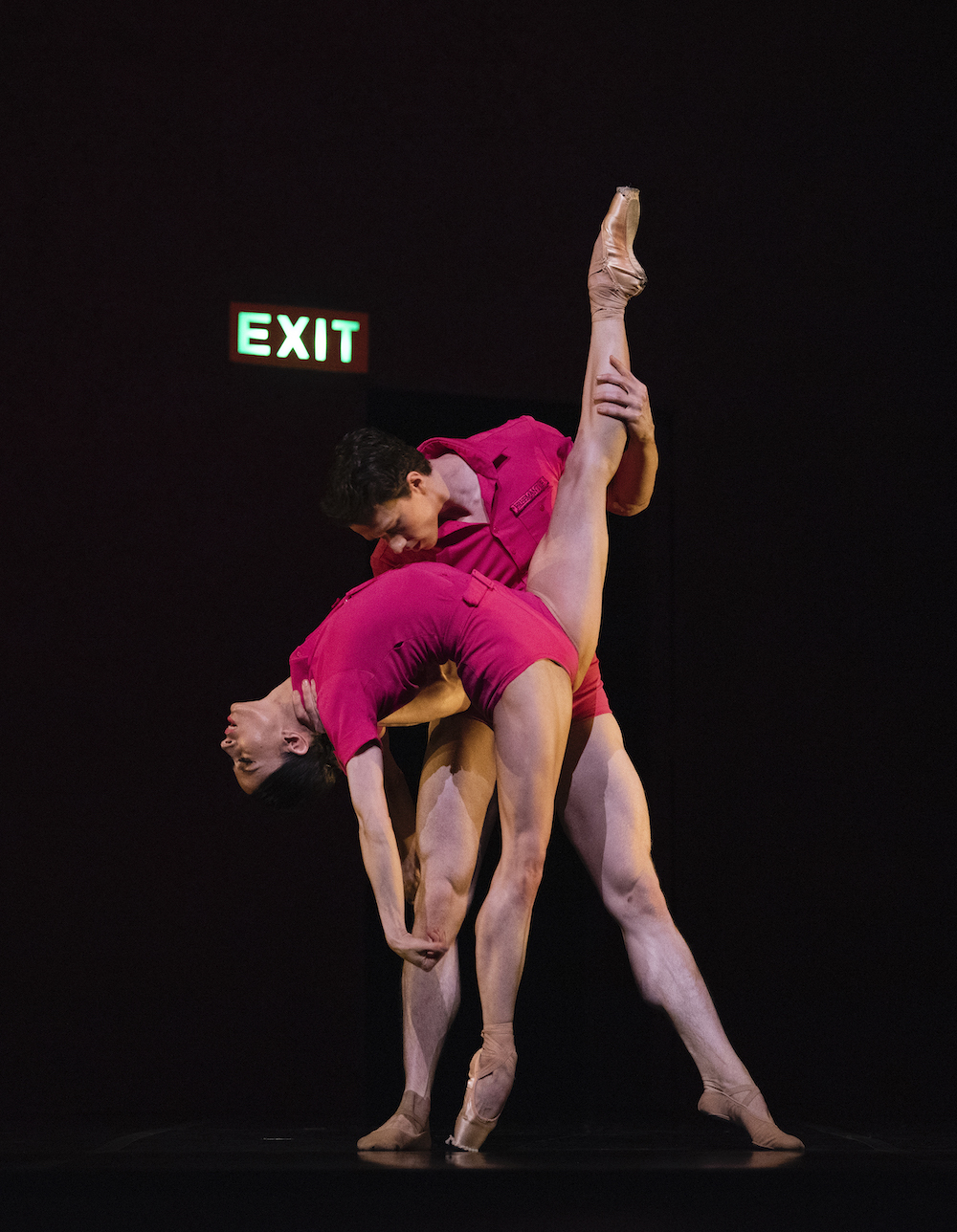

The dancers weren’t too shabby either. McIntyre paired Benjamin Freemantle, who exquisitely portrayed his grandfather in Your Flesh Shall Be A Great Poem, with Dores André, one of the company’s most intensely dynamic ballerinas. They opened the piece with a lengthy pas de deux that was both passionate and athletic. The music was lushly dark with dreamy exchanges between piano and woodwinds, the piano growing more and more dramatic. A kiss – heavens! – exchanged. Another kiss. And another.

Dressed in magenta shorts and short-sleeved shirts, the dancers were surrounded by a set that starkly resembled the underside of a massive concrete structure, a solitary green neon exit sign glowing upstage center left, conjuring up Sartre’s Huis Clos. The duet receded and a line of male dancers in bobbed magenta wigs, pink shorts and white shirts entered in a line. They were like odd robots in regimental formation, parading to a bumptious shift in the music, which in turn became increasingly comical and dissonant. The male chorus seemed some bizarre cross between Soviet workers and carnival kewpie dolls.

The tympani boomed and the brass snarled. A second duet followed with Jennifer Stahl and Luke Ingham. This couple took on aspects of the chorus, in magenta wigs and white uniforms, their steps more formal, moving closer to the mechanical in long-legged and impressive formalism. The neon light disappeared, replaced by a huge “Exit” scrawled over the set, an arrow pointing the way out. The chorus appeared and disappeared, their shorts now blue, their wigs steel gray.

A third couple appeared. The formidable Esteban Hernandez and Wei Wang, all in dark gray, and revolving in swirling athleticism. Eventually, everyone collapsed in a large heap in the middle of the stage. McIntyre again: “As hard as we may try to prove otherwise, there has to be an end to it. Eventually, all those things just crumble into a pile.”

Moving from the vivid to the gray sexless and mechanical, this ballet equally could be a metaphor for the Soviet system and artistic realism that made Prokofiev’s life a misery and radically affected his music. Whatever your interpretation, the ballet was a powerful, engaging and thought-provoking work, performed by some truly exceptional artists.

The program opened with Edwaard Liang’s metaphysical The Infinite Ocean, a near acrobatic work for ensemble and two lead couples, and closed with Harald Lander’s charming work Etudes, based on the formal and technical demands of ballet class in a loving nod to the intrinsic beauty of the dancer’s everyday world and the magic of the stage.

– Jaime Robles

San Francisco Ballet’s Program 3 continues through February 23. For information and tickets, visit sfballet.org.