Translating a translation highlights the fragility and multiplicity of meaning. A coproduction of Hope Mohr Dance and ODC Theater, extreme lyric I directly challenges the stability of gender and identity by embodying Anne Carson’s translations of Sappho. Although Mohr intends to “shed postmodernism with this work and investigate the lyric,” a precise, definable sense of self, the self implied by the I of the title, remains just out of reach. Sappho’s poetry, which exists in the original Greek mostly in broken fragments, proves to be a powerful collaborative underpinning for Mohr’s hybrid language- and movement-based performance.

Carson’s translations, collected in If Not, Winter and published in 2002, are unique in the way that gaps and absences in language are visually acknowledged. Brackets and generous spacing on the page demarcate where language has been lost to time, and invite the reader into an imaginative relationship with the poet. Similarly, extreme lyric I observes the loss and reconstruction of self, reclaiming the voice of a mysterious but over-historicized ancient artist who arguably transformed the landscapes of both poetry and gender.

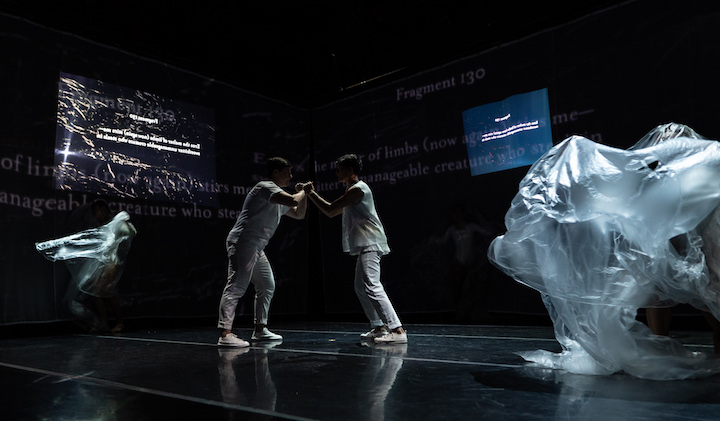

Performed in the round for small audiences at ODC Theater on October 4, this 45-minute ensemble piece brims with polysemous identities that burst in and out of self-discovery. It begins literally behind a veil, four sides of a translucent panel framing off a square arena. Four dancers shrouded in plastic sheets wander, specter-like, through a sort of primordial haze. Projected fragments of Sappho in Greek and English undulate along the panels. A murky soundscape by sound designer Theodore Hulsker drones and tinkles with faint echoes of half-formed melodies. The audience watches this strange aquarium, hints of bodies and limbs brush against the sensual and familiar. Crinkles of plastic as the dancers move add shards of noise and dissonance to an already indistinct scene.

After a few minutes, two performers emerge from the edges of the theater and press up against the fabric panels. They speak short, terse, third-person statements in “a litany of possible Sapphic identities and states of being”: “Sappho is obsessed”; “Sappho wants to die”; “Sappho’s heart is flying out of her chest;” and, perhaps most aptly, “Sappho is just out of reach.” The duos’ voices overlap and weave together a complicated narrative of self-deconstruction.

Language continues to flow forth. The performance text, co-written by Mohr and writer Maxe Crandall, intersperses Sapphic fragments with contemporary, casual speech to ask questions while swinging between ancient and modern modes. The performers experiment with postures of individual and collective power and appear to lurch in and out of control of their bodies. At times, the mood is hallucinatory and incantatory, building mystery and momentum.

Suddenly, the four fabric panels drop to the ground in a stunning moment of revelation; the audience members now look at each other across the arena, become self-conscious, and then refocus on the four dancers who remain onstage. The dancers, now freed of their plastic cloaks, take off into a new freedom, breaking into varied formations and alternating their relative agencies. The choreography demands attention as dancers create stances of ecstasy, desire, gratitude and exaltation. Moments of hushed whispers and ritualistic chanting (most strikingly a unison chant of Sappho’s most famous Fragment 16) echo the mystical incantations heard earlier. Dancers drape over each other and then pull away, sometimes moving another’s limbs, sometimes carrying the full weight of another body. As always in Mohr’s pieces, there is at times a sense of improvisation, fluidity, and ephemerality.

The ecstatic mode is propelled by percussive music, which, surprisingly, is twice punctuated by a slowed, almost tentative version of the 1993 pop hit “What is Love,” by Haddaway. Apart from suggesting one of the overarching questions of the piece, the song, conventionally “lyric” in its aesthetic and narrative, acts like a familiar anchor in the midst of an otherwise chaotic and fragmented experience.

The entire performance peaks in a sublime surreality when the two speakers reprise onstage, this time holding baskets full of pink and orange dahlia blossoms. The sensuality of these textures and colors suggests a more prescribed or traditional femininity, subverted at the very end of the piece when all six performers place a blossom in their mouth, chewing and swallowing it before marching offstage.

Mohr’s dynamic, multi-generic performance remixes both lyric and epic modes. The titular I transforms and transcends itself constantly. Sappho and Carson coalesce in movement to evoke a constant search for self and a lingering sense of absence, all at once.

– Dasha Bulatova