A surfeit of riches

The San Francisco Friends of Chamber Music hosted their annual extravaganza this past Sunday, Sept. 25, showcasing 35 different groups on four stages at the War Memorial Veterans Building. Running from noon until 8:00 p.m., this year’s free event delivered a good look at the variety of top Bay Area talent, and also focused on the history of the quartet form.

Once the quarters of the SF Museum of Modern Art, the Veteran’s building is next door to the SF Opera, its sister building. It re-opened last year after a retrofit and remodel with newly refurbished spaces that included two brand new concert halls on the fourth floor along with the main Herbst auditorium and the second floor “Green Room.” The acoustics have improved measurably, and it was a distinct pleasure to hear small groups filling large spaces with a dynamic sound.

Once the quarters of the SF Museum of Modern Art, the Veteran’s building is next door to the SF Opera, its sister building. It re-opened last year after a retrofit and remodel with newly refurbished spaces that included two brand new concert halls on the fourth floor along with the main Herbst auditorium and the second floor “Green Room.” The acoustics have improved measurably, and it was a distinct pleasure to hear small groups filling large spaces with a dynamic sound.

The musicians were organized by category, as they have in past years: early music, traditional chamber repertoire, contemporary music, and jazz. Alongside those divisions the festival opened with a lecture by musicologist Kai Christiansen on this year’s theme, or field report, titled “The String Quartet—The First 250 Years,” followed by nine separate concerts by as many groups, a veritable marathon of four-part string writing co-curated by Christiansen and violist Susan Bates.

That development and history was fascinating, and ran from Haydn at noon on up to a Michael Jackson string quartet (!) in the evening, but some of the outliers of the form were also provocative. In no particular order I zigzagged from one 45-minute set to another, enjoying two duos, three trios, and three quartets (and that was, sadly, only a quarter of what was on offer).

I arrived in time to hear martha & monica, a cello and piano duo that was performing a work by cellist Monica Scott on the recent death of a Russian free-diver. This was a riveting entrance to the afternoon, a deep Zen plunge into resonance, with Hadley McCarroll’s piano notes lingering in the air between the bitter grounds of Scott’s heavily bowed cello.

They ended with a slow descent of open strings, a tuning – or perhaps un-tuning – of a life.

The Delphi Trio took the stage to treat us to a magical camaraderie between viola, cello and piano. Pianist Jeffrey LaDeur spoke of the genius and tragic life of Czech composer Smetana. “It feels rhapsodic, as if we were improvising, but it’s actually very structured… He wrote it after the death of his daughter, and there is a final Tarantella, a dance of death, and then it ends in a funeral march. But this is really about transcendence of tragedy into joy.”

Liana Bérubé was dense in the low viola register, a reinvention of viola into a traditional Czech folk instrument, while LaDeur paced out a framework of careful chords. Cellist Michelle Kwon completed their soundscape, at times limning thin threads and at other times bowing fiercely.

Smetana combined major and minor modes convincingly. The piano was bright and coloristic, often playing major with trickles of golden notes, while at the same time Bérubé’s viola gave vent to the mourning and yearning of Eastern European minor. This was complex and mercurial, layered and storming and then suddenly simple and charming, and it was if one could hear the voices of children at play… and their echoes, and softer echoes. It was lovely and rather disturbing.

Moving two floors up and two centuries forward, the A/B Duo performed works that had been written just for them, capitalizing on their strange, or even awkward, timbre. Meerenai Shim gave sharp breaths into a contrabass flute, a re-curved instrument that rested on the floor and curved above her head, and Christopher Jones performed on percussion. There was a reversal of expectation, with the extremely low flute delivering percussive breaths against the beat of slack drum. This was not meant to be either pretty or lyrical, but explored sharp densities and monotonous rhythms, a modern tribute to the ones and zeros of an electronic landscape.

And finally I delved into the four-string quartet form, with The Telegraph Quartet performing Dvorak. Here was a master of the form and a young quartet who were absolutely passionate. Cellist Jeremiah Shaw brought thick loam to his C string, and second violinist Joseph Maile showed us the bottom of his register with a sound like bourbon and burnt enamel (okay, perhaps I was getting thirsty after three hours, but his sound was remarkable). Violist Pei-Ling Lin and violinist Eric Chin gave it edge and zest, and together they bloomed and whispered fearlessly.

This fresh foursome won the Grand Prize at the 2014 Fischoff Chamber Music competition, and Christiansen told us that they have also just won the prestigious 2016 Naumberg Competition.

He introduced the next young group, the Chamber Music Society of San Francisco, which is only three years old but already finding its path. They continued up the timeline of the quartet form from Dvorak’s sturdy Czech/German creations to Ravel’s soft colors and harmonic experiments.

“By the time Ravel wrote this quartet,” offered violinist Natasha Makhijani, “he had spent half of his life at the Paris Conservatoire, and [the conservative Director] wanted him out. This unusual quartet was written in response to the impressionism and changing art of his time. He hoped to finally win praise and the [Prix de Rome] competition, but instead this quartet was called ‘a stunted, badly balanced failure.’ Ravel was forced to leave the school, and that was a good thing, because the French love a rebel. Debussy, a supporter of the younger composer, begged him not to change a note.”

This is a fearsomely difficult quartet to play, requiring masterful balance along with virtuosity. Violinist Jory Fankuchen, violist Clio Tilton, and cellist Samsun Van Loon joined Makhijani for a gorgeous ensemble sound, and together they wove a spell that transported us to a realm like that of dreams. Here they laid out emotional truths in a language of ancient modes and fresh whole-tone scales where each phrase felt like a poem.

The first movement filled the Green Room with the exotic warmth of Rousseau’s North Africa and Gauguin’s Tahiti. Then pizzicatos and trills mimicked the warbles of birds, and whole tones and tremolos filled the upper air.

This was a first class performance of a luminous work.

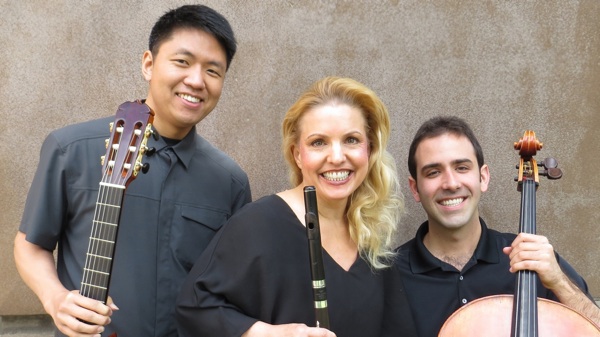

Afterwards, it was back up to the fourth floor Atrium, where the Black Cedar Trio explored a choice timbre. This is an unusual flute/guitar/cello threesome that plays both period music and a lot of fresh compositions.

Afterwards, it was back up to the fourth floor Atrium, where the Black Cedar Trio explored a choice timbre. This is an unusual flute/guitar/cello threesome that plays both period music and a lot of fresh compositions.

Flutist Kris Palmer described their first composition. “By day composer Durwynne Hsieh is an MIT trained molecular biologist, and by night he is a composer. Here is his Miscellaneous Music, which we commissioned. The first part is Möbius Movement, a circular path with just a single side.”

Long phrases with even-handed notes wound their curious way up and down Palmer’s African blackwood flute, mirrored by Steve Lin on guitar and Isaac Pastor-Chermak on cello. There was some of the toil of insects in this, and the firm bounce of summer grass, and even a touch of pop.

Introverted Interlude was deliberate, with a guitar’s golden notes at odds with lush flute and long cello notes. There were slow chords, piquant and questing, that reminded one of Ravel. And Five Fun Facts was silly and satisfying, full of pratfalls and insider musical jokes.

After, the composer stood and was applauded.

While the string quartets downstairs had moved on to Shostakovich and then were completing their journey with contemporary luminaries like Terry Riley and Philip Glass, more unusual ensembles were exploring their own paths.

Four members of the contemporary group Earplay filled the Green Room with delicate textures. Violist Ellen Ruth Rose joined flutist Tod Brody in the odd Salad Bar by Ellen Ruth Harrison. Each movement was titled after a salad, from lush tomato to the cool crunch of cucumber and on to prickly dandelions, and it was clever how the instrumentation so well fit the textures of a salad. Salads are, after all, the epitome of odd bedfellows, where leafy, crunchy and nutty are all drizzled with some unifying oil. The dissimilar viola and flute were well suited for this.

Composer and clarinetist Peter Josheff wrote Sutro Tower in the Fog for flute, piano and clarinet. He discussed his impulses before performing it with Brody and pianist Brenda Tom. The five movements had arc and drama, but what was most perfect about them was, again, the immediacy of their textures. There were lovely unisons and even lovelier dissonances, cool and soft and foggy.

They ended with Bruce Bennett’s twasome for flute and clarinet, and it was a froggy frolic, leaping and self-satisfied.

Before I slipped out into the evening there was one more treat, and an unexpected one – the medieval sound of Vajra Voices. This seven-voice women’s ensemble, led by Karen R. Clark, delivered the religious music of Hildegard von Bingen in slow, modal statements. Their pure harmonies explored and hallowed a women’s heritage that is nearly one thousand years old, but it felt not only contemporary but almost electric.

Next year there need to be four of me!

—Adam Broner

Photos, from top: martha and monica: Hadley McCarroll, piano, and Monica Scott, cello; photo courtesy of the artists.

The Delphi Trio, from left – Michelle Kwon, cello, Jeffrey LaDeur, piano and Liana Bérubé, violin; photo by Jason Ly.

Telegraph Quartet, from left – Jeremiah Shaw, cello, Joseph Maile, violin, Pei-Ling-Lin, viola and Eric Chin, violin; photo by Eric Chin.

Black Cedar Trio, from left – Steve Lin, guitar; Kris Palmer, flute and Isaac Pastor-Chermak, cello; photo courtesy of Black Cedar.