A cycle of sound and memory…

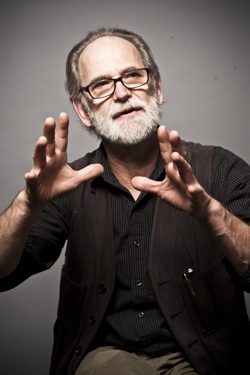

Trimpin, the single-named kinetic sculptor, just finished a year of residency at Stanford, courtesy of Stanford Lively Arts. Along with his work with students and with the electronic music center, CCRMA, he was commissioned to develop a performance project that drew on autobiography, years of creating kinetic sculptures and musical instruments, and material from a French concentration camp.

Trimpin, the single-named kinetic sculptor, just finished a year of residency at Stanford, courtesy of Stanford Lively Arts. Along with his work with students and with the electronic music center, CCRMA, he was commissioned to develop a performance project that drew on autobiography, years of creating kinetic sculptures and musical instruments, and material from a French concentration camp.

Part retrospective and part political art, the Gurs Zyklus (Gurs Cycle) was at heart a memorial service to the victims of fascism, beginning with the assassination of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca and ending with letters from Jewish prisoners.

Last Saturday, May 14, as Stanford’s Memorial Theatre darkened, a Hebrew word, machzor, appeared on the center of three screens, a book of prayer. Four women entered and began ferrying 12 vases to blue-lit pedestals at the front of the stage, then, covering their heads with their shawls, seated themselves in the darkness in a row.

Water began to drip from the high proscenium down into the vases, dental plosives of sound tuned like pitched drums. The four women exchanged short exhalations, stressing the unvoiced breath rather than the vowel, and then sharper clacks of wood on wood layered over the softer chuffs and drips, two notes raveling the fabric.

Single letters appeared on the screen synchronized with the wooden clatter and we became aware that old Morse code was spelling out a message: “Give him coffee, plenty coffee.” This was a code phrase used by Franco to order the death of Spain’s greatest poet, Lorca.

These acoustic inventions were layered in a fabric of coincidence and history as much as sound, and the performance proceeded to unveil Trimpin’s response to his German village’s silence. When he was a child he followed train tracks out of town to see a derailed train, then cut cross-country on the return. Stumbling over overgrown headstones, his questions brought reluctant answers—it was a Jewish graveyard, and the Jews were all gone to Gurs, a concentration camp in the French Pyrenees. The combination of train cars lying on their side, stones chiseled in Hebrew and a lost people made an indelible impression. In an artist’s conversation hosted last week by Stanford, Trimpin described the strange gaps and taboos of that time—the pages of their fourth grade history books were razored out from 1933 on.

Directed by New York-based performance artist/playwright Rinde Eckert, the Gurs Zyklus began with references to the Spanish Civil War, as refugees from that conflict escaped into France only to be imprisoned by the French at Gurs.

American composer Conlon Nancarrow, an early innovator on player piano and mechanistic music, was an important influence on Trimpin. After Nancarrow once mentioned that he was imprisoned in Gurs after fighting alongside the Abraham Lincoln brigade, Trimpin renewed his need for some sort of remembrance or closure, a cycle that was completed when he obtained letters from that camp.

Other elements included hanging balls of glass, a reference to Kristallnacht, and long bridge-like teeter-totters with rolling speakers. Those broadcast the reading of prisoner letters and Trimpin’s recordings as he reprised the train journey south to Gurs.

Trimpin added a fire section to his instruments with glass tubes that resonated from flame speakers. The paired “fire organs” delivered exquisite rumbles, rich in overtones and similar in structure to the human voice—and with a similar range, three and a half octaves.

At the former camp, Trimpin found that Gurs had been bulldozed, and trees planted there. In a search for traces of history, he took pieces of bark from mature sycamores, organic witnesses to the past, and developed an algorithm for “reading” the bar

k onto his player pianos, a curious way of giving voice to those normally voiceless.

Despite all of the activity

anel/jscripts/tiny_m

ce/themes/advanced/langs/en.js” type=”text/javascript”> mdash;the rain falling, the letters from prison, the paper crumpling—there was a feeling of helplessness, a distancing of history through electro-acoustic interfaces.

Or perhaps that stunned feeling reflects the reality of collaboration with evil: for most of us it comes down to the lack of political will or courage, or a very European insularity. Trimpin’s Gurs Zyklus is a reminder of degrees of culpability and that, in this small world, we may all be “driving the get-away car.” But we can steer.

—Adam Broner

Photo top: Trimpin, photo by Toni Gauthier/Stanford Lively Art. Photo bottom: singers Linda Strandberg, Katya Roemer and Thomasa Eckert rehearsing Gurs Zyklus, photo by Nic Dahlquist.