When dreams come knocking on the portals of perception

There is a space between waking and sleeping when ones’ thoughts gain a symbolic and surreal brightness, and when images are as small and vivid as the far-off sounds of children in a schoolyard. That hypnagogic state came to life last night at Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall.

Part act of rebellion, part musical portrait, Philip Glass’ Einstein on the Beach fused synthesizers, singers, mesmerizing sets and elegant choreography into an art form that was revolutionary when it first appeared in Avignon, France in 1976. It is currently undergoing a renaissance, thanks to the joint efforts of Cal Performances and six opera houses from the USA, Canada and Europe. Matías Tarnopolsky’s three years as director of Cal Performances has been marked by several large undertakings, and this ranks among his most ambitious.

When Marcel Duchamp followed the furor around his “Nude Descending a Staircase” by hanging a urinal on the wall of the New York Armory in 1913, he not only scandalized the established art world, but opened a door into found forms, thus framing the artist in the moment of intention.

Philip Glass did something similar when he and Robert Wilson, who became his co-creator and director/designer, rented the Metropolitan Opera House for their mélange of found-form libretto, formalist theater, and minimalist musical figures graced with the choreography of Lucinda Childs. Einstein on the Beach dispenses with the needs of conventional opera, what Glass once described as “a profoundly different expectation of musical theater.”

Disconnection is the essence of this epochal work.

An autistic 14-year-old wrote its jumbled text, augmented by advertising flotsam and occasional narration. The choruses sang numbers and solfège (do re mi fa’s), and there is one aria that had no words at all. (That aria, sung by Hai-Ting Chinn, was an uplifting moment.) The music is also disconnecting, loud and repetitive gestures with glacial pacing.

An autistic 14-year-old wrote its jumbled text, augmented by advertising flotsam and occasional narration. The choruses sang numbers and solfège (do re mi fa’s), and there is one aria that had no words at all. (That aria, sung by Hai-Ting Chinn, was an uplifting moment.) The music is also disconnecting, loud and repetitive gestures with glacial pacing.

The two narrators are nearly automatons, jerky and dressed in identical desexualized office attire. Over a primal machine drone, they take turns reciting fragments and numbers.

“It could be very… fresh! It could be a… balloon!”

“One… forty eight… three hundred twenty one thousand… “

In the trial scene a lawyer swings a brief case, turns to smile brightly, and then cuts off the smile like a knife. He crabs halfway across the stage in jerky repetitions.

And the dancing reinforces that disconnection, with long patterns of steps and twirls, but with no interactions. Each is lost in their own movements.

The staging is clever and constantly engaging, and there is obscure movement and the feeling of a plot, although it is not clear at all what the action is. But there is movement and a slow montage of emotions, with the scenic intensity of picture postcards.

The question is whether that works as opera.

Surprisingly, it works very well. The characters evoke a generation’s increasing isolation, and their frenetic movements speak to us of the fears and fascinations of the early atomic era. Over time, the music begins to connect to us at a proto-musical language, with simple progressions and fluid rhythms touching some primal level. Gradually, solos take over the machine language, first a flute duet and then long hours of violin solos by Jennifer Koh, seated on the edge of the stage in an Einstein fright wig and makeup. In the ivory tower scene, an alto sax solo by Andrew Sterman grows into passionate phrases, as the chorus members walk onstage to gaze up at the stark 50’s brick building, and then depart by ones and twos.

The dancers may be disconnected, but they shape the portents of society. Spin, polarity and charm, their perpetuum mobile is both sub-atomic energies and a glorious celebration of the music, a unified field theory of dance and dramatic intent.

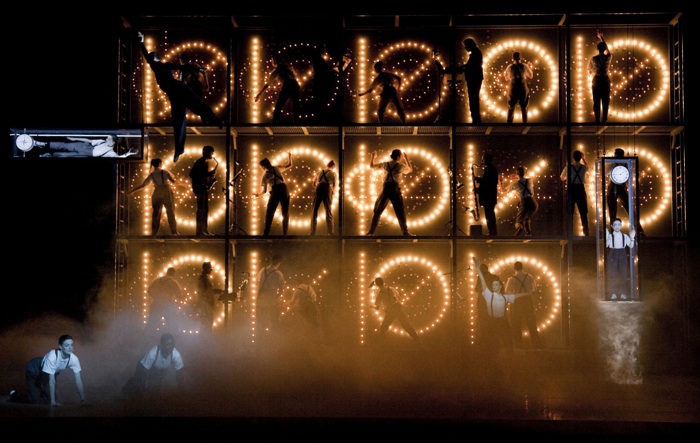

And lastly, we are moved by the stark, surreal and symbolist sets, building to the shocking beauty of the final scene, the three tiered “guts of the machine.” Though this work is immersed in the seventies, its themes are as timeless as Mozart.

—Adam Broner

Photo top of Kate Moran and Helga Davis with chorus members, photo by Lucie Jansch; photo below, final scene, by Lesley Leslie-Spinks.